Fencing and Fencers in Paris, 1892

De Kay, Charles. Fencing and Fencers in Paris. The Cosmopolitan. Vol. 12. No. 3. January, 1892. The Cosmopolitan Publishing Company. New York.

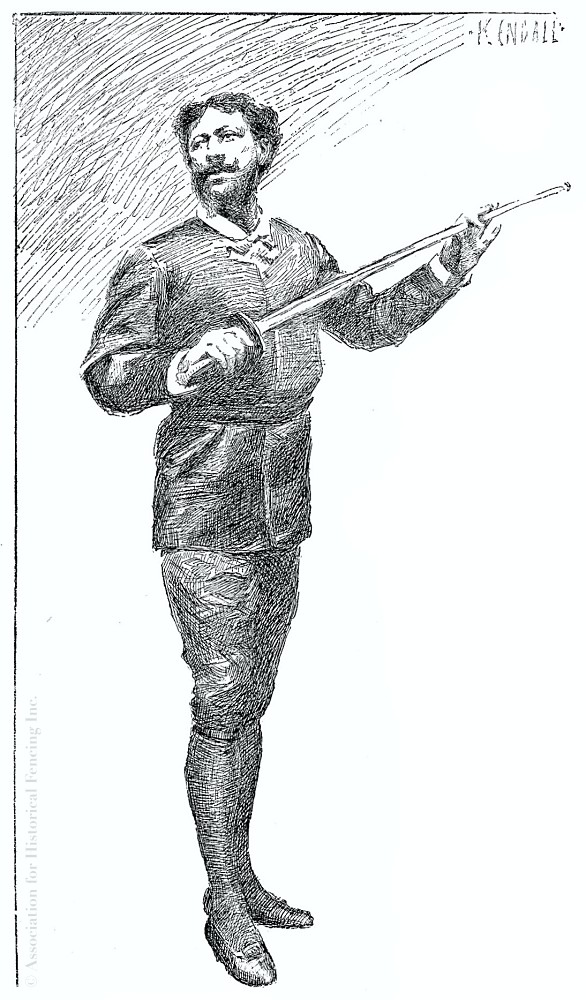

Most images signed “Kendall.”

Please refer to our Copyright and Usage guidelines.

FENCING AND FENCERS IN PARIS.

BY CHARLES DE KAY.

By this time we should be prepared for surprises in France. How often have we heard that the republic was one in name only and that the monarchy or the empire was certain! Well, the duel is going out and physical exercises are all the rage! Just now the two great republics of the old world and the new are exchanging ideas in athletics, the results of which may be farther-reaching than a war. The French have been seized with a passion for exercise hardly less absorbing than that which still keeps Englishmen foremost in cricket and in rowing, notwithstanding occasional defeat by oarsmen and cricketers from Australia and America.

In the army great attention is being paid to gymnastics and every man is supposed to serve. Societies for gymnastic exercises are formed in many towns where heretofore the young men grew up without any training whatever. The bicycle is very popular; yachting and rowing are increasing in favor; lawn tennis has the sanction of good society and has broken down the barriers which hitherto have hedged about the young unmarried lady, well bred or of noble birth; foot races, swimming races, canoe races now vie with the monopoly long held by the turf as events that interest all classes and they even stimulate those who only live to bet. It was in consequence of this change on the part of the French that Baron de Coubertin, having visited the United States in behalf of his government, induced a team of long-distance runners, sprinters and jumpers belonging to the Manhattan Athletic club of New York to enter the games at Paris last Fourth of July. Their victory was complete but the French intend to profit by the defeat, as they have profited by their overthrow in 1870 at the hands of Germany.

In one branch of athletics the French have excelled, however; for the last two centuries, if not three, they have produced the best men in the sport of fencing, while their preeminence seems to have increased during the present century step by step with a relative preponderance over other nations on the European continent in literature and the fine arts.

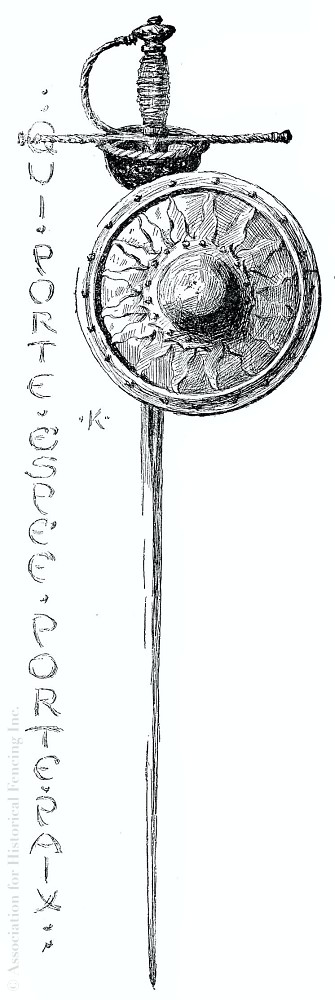

Note.– The arms on this page are reproduced from the Spitzer collection by courtesy of Madame Spitzer, and the portrait on page 362 through the courtesy of the New York Fencers Club.

One rarely hears of a great swordsman in Spain while those of Italy are few compared with the French. Paris throws a spell, she has a power of attraction, over Italy and Spain, which draws many of the finest minds of those peninsulas to her in their youth and turns them into Frenchmen, just as she draws Provençals from the south, Bretons from the west, Swiss and Austrians from the eastward and Bavarians and Alsatians from the north. She is at present the centre where the greatest number of good teachers of swordsmanship can be found and where one may encounter the greatest variety of amateur fencers. And from this centre swordsmanship as a science has radiated in all directions. The chief instructor at Moscow is M. Pons, the son of the more famous master-at-arms of that name. In Rome the methods of Signor Masaniello Parise are largely if not exclusively French, and the same may be said of Signor Pini, a very skillful swordsman of Leghorn. The old Italian system of fencing is preserved in Naples more out of patriotism than because it commends itself to any large body of amateurs. So far as fencing exists in England its style is exclusively French, while there is no difference whatever between the teaching of Belgian and French instructors. In Mexico, Brazil and the Argentine the teachers are French. Finally, we of the United States have begun to enter into the sport, using, like other countries, the rules and regulations established by the masters of France in the present century.

Here, then, we find the younger republic exchanging with ours one old and highly perfected form of athletics for a number of exercises, which have taken comparatively few years to develop under the vigorous fosterage of Americans. Neither New York nor New Orleans nor Boston nor, Philadelphia has ever been long without some professor of the science of the sword; but until 1875 no teacher of that science in North America could make his living by his profession alone, and until 1882 no large number of amateurs could be kept together anywhere to practise the art. The Fencers Club of New York, founded in 1883, began the serious introduction of a game, which hitherto had languished in the United States to such a degree that its existence might well have been ignored. At present the club has nearly 200 members. Schools and clubs for athletics patronize the game and four masters make comfortable livings in New York by teaching fencing alone. If, in other kinds of games demanding tact, patience, trained muscular power and brainwork, Americans have shown themselves singularly proficient; if they have excelled in billiards, rifle shooting, bicycling, rowing, yachting and pugilism, there seems no reason to doubt that as soon as fencing becomes generally established individuals gifted with a phenomenal aptitude for sword-play will be developed, who may in their turn defeat the best amateurs that France can send against them.

Fencing itself is in France a unit; that is to say, nearly everybody is agreed on the main lines of the game, while a great deal of individual difference may be observed in the style of different professors. But this being said, the professors may be divided broadly into the military and the civilian. Sorrowful to relate, there is a quarrel between the professors of the art who instruct in the military schools of fence and those who teach citizens in Paris, Lyons, Marseilles, Bordeaux and other towns large enough to support a fencing floor for civilians. The army has a college or high school of military gymnastics, in which fencing cuts the best figure, the headquarters being near Paris at Joinville-le-Pont. Here are formed the masters-at-arms who are distributed on graduation to the various regiments of engineers, artillery, cavalry and infantry, in France and Algiers. At the Ecole de Gymnastique Militaire of Joinville-le-Pont not only the officers and subalterns but the corporals and men are obliged to practise thrice a week. They fence according to the principles laid down in a Manuel d’Escrime approved May 18, 1877 by the Minister of War—principles which do not differ in any important point from those taught by the civilian professors of Paris. As is the case at West Point and Annapolis, more men are graduated each year than possibly can get places as professors of fence attached to regiments. And there the shoe pinches. For these graduates enter into competition with the prevots or lieutenants of the civilian masters in Paris and the larger cities, lowering the salaries; or they become direct rivals of the masters by setting up for themselves on the strength of their diplomas from the army school, while the favored ones who get places with regiments are also glad to teach civilians, in rivalry with local instructors who have no salary from the state.

To meet this feature of the situation a number of civilian masters, some of whom had been before that period at the school of Joinville-le-Pont, met in 1886 to discuss, and ended by founding the Academy of Arms.

They were twenty in all, including the Merignacs, father and son, Jean Ayat, Camille Prevost, son of the old master of that name, and one or two more professors of the first class. But, as in all cases of the kind, the twenty Maîtres Titulaires, as they called themselves, included respectable names which did not represent great swordsmen; and this gave deep offence. Then the twenty added to their academy certain maîtres adjoints, membres correspondents and membres honoraires, the first representing associate members, as it were on probation. They made the Minister of War the president of honor, elected General Lewal, M. Ducreux of the bar and a strong amateur, M. Fery d’Esclands, vice-presidents of honor, and gave the title of honorary master to five elderly swordsmen. They themselves are called “Masters-at-Arms of the Academy of Paris,” and must be twenty-five years old and have exercised for at least two years their profession in Paris without a salary from the state. Unfortunately, or fortunately, its right to decree a diploma or to establish by election the quality of a given swordsman has been denied by a great many fencing teachers in Paris, so that the name of Maître Titulaire or Maître Adjoint of the Academie d’ Armes does not carry with it, as yet, the authority that it may when its scope has been widened and the large majority of good swordsmen of Paris have been brought within its limits. The antagonism to the military school, which it has developed, is at least unlucky, for most of the good fencers have at one time or another belonged to the army, and the later graduates of Joinville-le-Pont learn to regard the academy as their foe.

The military men who live in Paris are by no means forced to enter the civilian fencing floors in order to practise with experts and obtain exercise. At the Cercle des Armees de Terre et Mer—that fine club founded by General Boulanger on the Avenue de 1′ Opera- there is a small but excellent fencing floor governed by M. Berretrot, Adjudant-Professeur d’Escrime, formerly one of the professors at Joinville. Here the professor and four assistants give lessons and exercises to 300 or 400 members of the military and naval club. In winter the attendance runs up to eighty or 100. Amateurs who often figure in the grand exhibitions frequent this very convenient salle d’armes. Such are Commandant Derue, formerly of the school at Joinville-le-Pont, Lieutenant Bouchard the artist, M. Fery d’Esclands, M. Cremieux-Foa, captain in the Eighth dragoons, M. Deruis, lieutenant in the artillery, General Rebillot of the artillery, M. Rendu, an officer in the Eleventh chasseurs (foot) and Lieutenant Kopenhague of the staff.

Nor is the military club the only place where officers of the army can fence. In the cavalry barracks on the Champs de Mars at the Ecole de Guerre an excellent salle d’armes is ruled by M. Michon, where about 200 officers inscribe their names every year, and between forty and fifty use the floor daily. Fencing is not obligatory on officers, but with these floors the military and naval men can regard with equanimity the efforts of the Academie d’ Armes to counteract the advantages the army professors possess. If the Academie d’ Armes shows a very decided coolness toward the military professors, ignoring them for the most part in the assaults given in public, and claiming superiority as fencers and teachers, the military men are not slow to return their scorn with interest, and maintain that the academicians- elderly men for the most part—who as experts no longer care to risk reputations painfully acquired and tenderly guarded, are neither more nor less than afraid to en-counter such vigorous, well-skilled fellows as they!

The general movement in athletics has its echo on the fencing floors. A little monthly magazine, edited by a fencer, M. Emile Andre, and called L’Escrime Francais, now in its second or third year, tries to bind together the civil and military masters and the larger world of amateurs. Among its many good suggestions is a congress of fencing men, which shall meet at Paris in order to establish relations between the various fencing clubs of the country, and fix more exactly the rules and regulations to govern public assaults at arms. Such a congress might take up the idea of the Academy of Arms and erect it into a senate of swordsmen.

There is still another organization in Paris which, like the Academie d’Armes, has no building or office, but exercises, it is likely, much more influence for good on the general art of the sword. The Academie d’Armes sets out to benefit fencing at large, but is hampered by the obvious suggestion of personal advantage and advancement for its maîtres titulaires. The society now to be mentioned exists simply and solely to further the cause of swordsmanship. Its president is M. Hebrard de Villeneuve, its annual dues are very small, and its membership is very large, including, theoretically, all the amateurs and well-wishers of fencing without distinction of sex.

The Societe de l’Encouragement de l’Escrime gathers up professors, prevots, amateurs, persons who can be induced to subscribe, ladies and children, and enrols them for a small annual fee on its list. Its office and object are the patronage of fencing, by arranging public exhibitions, which may spread the taste for the game among French people and the foreigners who seem to take possession of Paris to the exclusion of the French. If a distinguished swordsman comes to France it is the proper thing for the Societe de l’ Encouragement to arrange for his appearance in such a way and with such an audience that the best masters of Paris will not refuse to appear with him. It has no building, gallery, or other establishment, but is simply an agency for the furtherance of the cause of swordsmanship.

Meantime it may be noted that a similar organization has been started in New York, called the Amateur Fencers League of America, whose office is to encourage fencing, “and to formulate and publish rules for the management of fencing contests in America.” So far its chief object has been to define what an amateur is; later it may become a more active body.

Little has been said of that which comes uppermost in the minds of people unaccustomed to the idea of fencing and clubs of fencers -the duel- because of its small importance. One has to live in France to realize how little duelling there is in a country supposed by many persons to reek with the blood of men unable to satisfy otherwise the demands of their own honor. Duelling is confined almost entirely to journalists, politicians and soldiers, and among these a duel is becoming year-by-year more a matter to be ashamed of than a boast. The influence of America and England has had much to do with this result, but one must not forget the curious fact that the game of fencing has hastened the decline of the duello.

It is a well-established fact that gunpowder gave birth to fencing as a fine art, because gunpowder drove out armor, and in the absence of armor it became necessary to defend the body with a narrow blade. Down to the Napoleonic era fencing remained a preparation for combat, and partook of the amusing but unpractical conceits imagined by Italian and Spanish masters of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The introduction of a light but strong mask proved a turning point in its history, for only then could many masters study with their pupils the finer points of attack and defence. The sword itself had then been shortened to the size it now holds, though Italians and Spaniards kept it long for a good while, and the Neapolitans still use a fleuret that retains a suggestion of the rapier. The foil as we now have it, the light mask and the glove, combined to turn fencing, formerly an art practised for the neater killing of men, into a sport, a game, a form of athletics less liable to dangerous accidents than any, and more directly personal and absorbing than the active amusements the world had hitherto known. This affected the duello in a way that was not foreseen.

Instead of widening the number of men who were confident in their own skill and sought quarrels in order to show that skill by wounding or killing others, the development of fencing as a sport spread the knowledge of the uncertainty of results in a duel. It gave people another interest than the old crude one of the wound that cripples or kills; it set the mind on intricate or beautifully simple movements resulting in a bloodless victory or a defeat that left no rancor. It encouraged good temper and comradeship, and opened men’s eyes to the fact that the swaggerer and swashbuckler, who figured in the old plays when fencing to kill was the fashion, was the than least to be feared if it came to serious business.

But there were certain technical modifications of the game of fence, which have exerted a direct pressure on the duel with the sword. The slender foil represents the slender duelling sword with a point but no cutting edge; hence in duelling the combatants stand far apart, for as there is no cutting blow nothing is gained by closing in. The fine game with the foil admits as points that count in the game only the blows that reach the upper breast fairly and full, rejecting as worse than no points the blows that touch the mask, the arm or the belt; hence in the game of fencing, as in other games, a number of rules have grown up which steadily repress forward rushes wild work outside the little target of the upper breast a or the blow that seeks to disarm the opponent. It stigmatizes the man who strikes after the other has made his own point, demands that the one who is hit shall proclaim the fact by calling aloud, and visits with disapproval him who strikes if the combatant has dropped his foil.

These and other rules of the floor have crept into the regulations that govern a combat with sharp swords, and modified them so much that if it comes to the terrain, after all efforts of accommodation are vain, a duel is one of the least dangerous of risks, compared with which steeple-chasing and football are games full of peril to life and limb As a rule, the umpire manages to keep the duellists well apart, so that the hand or arm is wounded; at signs of too desperate a rush he interferes and the first scratch usually ends the affair.

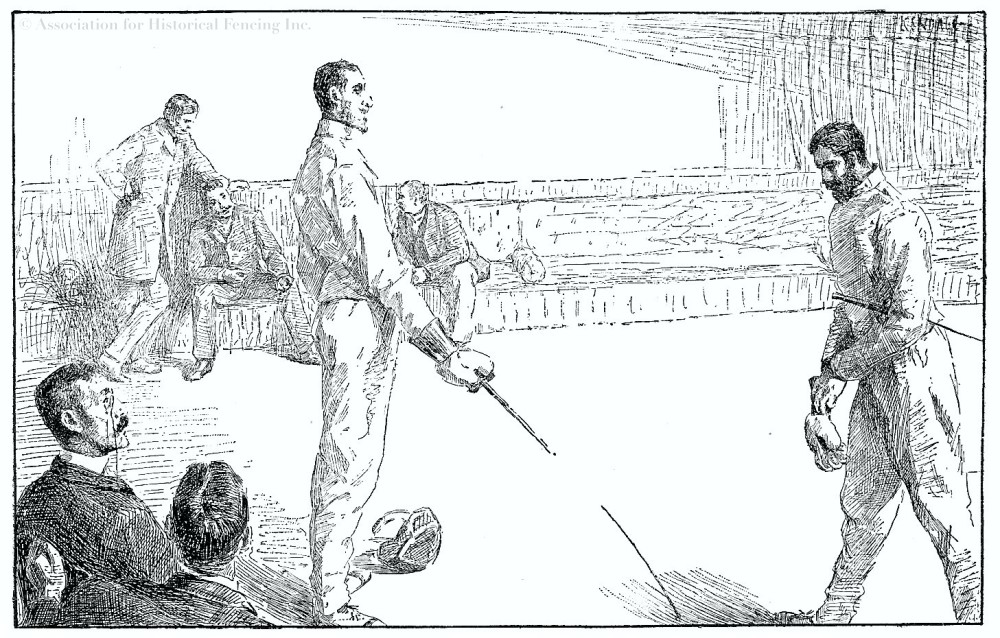

It would be invidious to affirm, if it were in strictness possible, which is the finest, best appointed, most agreeable fencing floor in Paris. The Ecole d’Escrime Francais in the Rue St. Marc, not far from the Bourse, is one of the most frequented, though its talented master-at-arms, M. Rue, is not a member of the academy. The scene at this salle is very animated between four and seven of an afternoon.

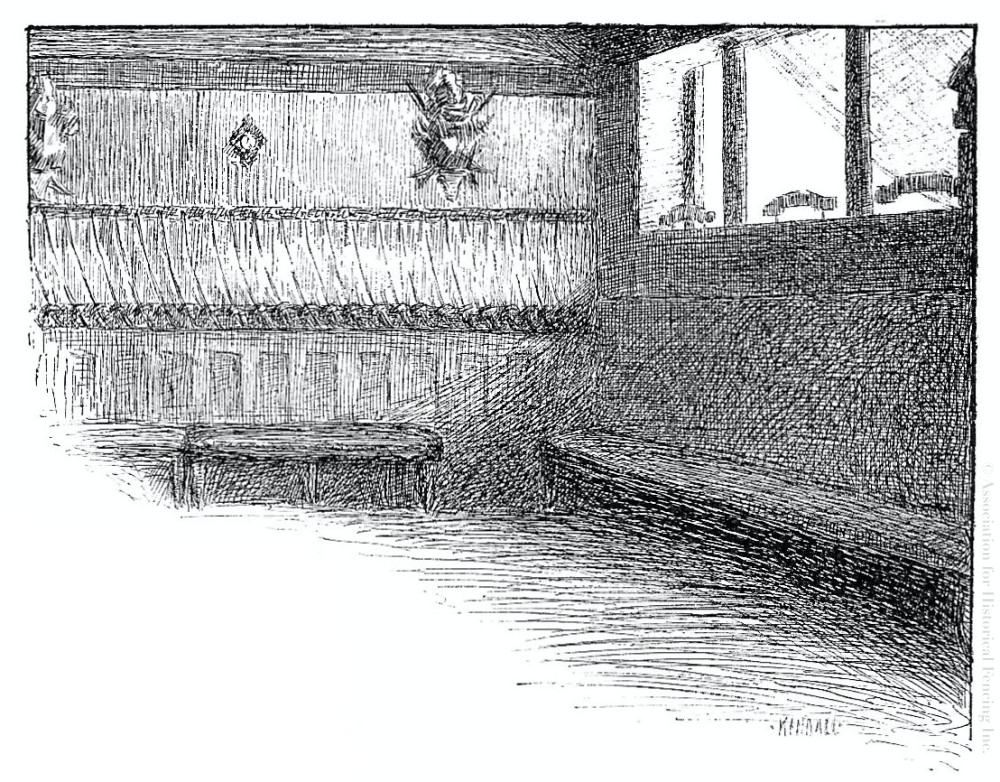

Another very large cercle for fencers is near the Louvre, and still goes by the name of Salle Mimiaque, though Mimiaque died in 1883. The school continues under M. Large, one of Mimiaque’s prevots. The grand fencing gallery contains ten planks for couples and the floor will accommodate about thirty men at once. It is lit by large windows on two sides and has really sumptuous lounging rooms, reading room, vestiary, lavatory, and a room for shower baths of various kinds. It is more nearly a club like the Fencers Club of New York than many of the cercles d’escrime of Paris that is to say, members have to be elected. They pay on entering twenty dollars, and an annual charge of sixty. Still, the professor and his prevots are allowed privileges that American clubmen would not relish. Members are expected only on Mondays, Tuesdays and Fridays, from two to seven in the afternoon.

Another large and fine Salle d’armes is that kept by M. Roulleau in the Rue des Pyramides, much frequented by Americans. M. Roulleau is one of the founders of the Academie d’Armes. Smaller in the dimensions of its fencing floor but not less renowned is the Cercle d’Anjou swayed by M. Jean Ant, a very accomplished swordsman. Its president is the Due de Lesparre, and it includes several men with high titles and old names, such as the Due de la Rochefoucault, Count Henri de Fitz James, together with a number of the names known in high financial matters. Among American members is Mr. Henry Ridgeway.

In the matter of titles, however, no club on the left bank of the Seine can vie with a little floor on the Rue de Bourgogne in the Quartier St. Germain. Its president has the very appropriate name of Bonnegarde, as if destiny had pointed him out for a swordsman, since the first and main care of the swordsman is not so much to have a good attack as a good guard. Its founders are the Baron Pierre de Coubertin, Marquis de la Mazeliere, Vicomte Robert de Rouge, Duc de la Rocheguyon, Comte de Ranchicourt, Comte Charles de Crisenoy de Lyonne, Vicomte Aurelien de Courson, M. Revel, Comte Charles de Diesbach and MM. Coppon-Mandar and De Bonnegarde. The list includes such old French names as Noailles Prince de Poix, Rochefoucault, La Motte, Orleans and Gramont. The teacher is an old cavalryman, M. J. B. Charles.

But the salle d’ armes which excites most interest in fencing men is that governed by the Merignacs, because the elder Merignac is still the undoubted head of fencing in France and the world. At times he is run very close by some ambitious fencer like M. Calmels of the school at Joinville-le-Pont, M. Michon at the Ecole de Guerre, M. Camille Prevost, M. Rue or another. Signor Pini of Leghorn has received a decoration as Chevalier of the Legion of Honor for the beauty and effectiveness of his bouts with Merignac last winter. Nevertheless the latter retains the absolute preeminence which has been accorded him for the last ten or fifteen years, and bids fair to hold it for ten years to come.

Even so summary a sketch as this would look incomplete if the fencing floors were forgot which are attached to great social clubs like the old “Mirlitons,” now dubbed the “Epatants ” or “stunners ” in the slang of the boulevards. Baron Hirsch having turned the old Mirlitons ” out of doors, the latter had to leave the Place Vendome, but they improved their case greatly by joining with the club that controlled the corner of the Rue Boissy d ‘Anglas, looking out on the Place de la Concorde. There is the terrace where the members of the old Club Imperial used to lounge and watch the gates of the Tuileries gardens fly open and the Cent-Gardes parade heavily, magnificently forth, followed by Napoleon III. and Eugenie. The building back of this terrace was completely remodelled, and a fencing gallery arranged in connection with one of the most complete and sumptuous series of dressing rooms, baths, etc., which can be found in Paris. Members of the club can become members of the fencing establishment by paying an extra charge, but no outsiders are permitted to use the gallery. Once a year the little theatre of the club is the scene of an assault at arms between professionals and amateurs, to which. outsiders may be asked by card of the club member; ladies are never invited to these exhibitions, nor are women ever permitted to make use of any club or fencing floor in Paris, contrary to the custom established in New York by the Fencers club, where a class of ladies takes possession of the floors and dressing rooms of the club thrice a week in the morning, and the male members are excluded.

The “Epatants ” is an interesting fencing club because its membership contains a large number of famous artists. M. Carolus-Duran is to be seen there almost every day, together with the landscape painter Billotte, whose portrait he painted with charming sympathy last year and showed at the new Salon. The artists Roll, Henry Reynaud, Clairin and Arcos are active members; the American artist Alexander Harrison is one of several who belong to the club but not to the fencing branch. One of the strongest amateurs in Paris is the artist Guignard who frequents this floor. The musicians of the club rarely fence, but an exception is M. Serpette, who has the reputation of wielding a foil hard to parry. MM. Paul Bourget, Guy de Maupassant, Fernaud-Boussenot and Paleologue are often at work in the fine quarters provided by the “Epatants,” where they find very capable instructors in M. Camille Prevost and M. Fillippi, who are assisted by a provot, M. Desglas. The amateur who holds the reputation of the floor high by his bouts in public with professionals is Comte de Lindemann, a French-man of Bavarian descent. MM. Guignard, Carolus-Duran and Serpette are counted among the strong fencers; Chabert, Vicomte Bretonneau-Clary, Comte Potocki, Legrand, Comte Emmery, Cottin, Fauche, De Sauvage and Du Tremoul are others well spoken of. The club has several thousand members, and the fencing branch about 15o.

Somewhat similar in organization, membership and name is the Cercle Artistique et Litteraire on the Rue Volney. Artists so preponderate in the Cercle Volney that the president, M. Paul Tillier, is a painter, while such well-known names as Bouguereau, Toulmouche, Henner, Luminais, Van Marcke, Veraestchagin, Olivier Merson, Tattegrain, Bonnat, Vibert and Carolus-Duran are on the list of members. The American painters Bridgman, E. L. Weeks and S. H. Parker are members. The teacher of fence is M. Gaillard. There is also a very large and well-equipped salle d’ armes connected with the Cercle des Arts et d’Escrime in the Rue Taitbout, where suits of armor, trophies and large racks of swords and foils give a lively appearance to an interior lighted from above. Here M. Hottelet, another renowned champion of the foil, instructs the members of the club with the aid of two prevots.

Fencing floors attached to social clubs have an advantage in that deficiencies are paid by the club at large and the resources of the club can be used to surround the fencers with no little luxury. Never the less the cercles of Paris which are exclusively supported by fencers seem to have more weight. The professor in such a club feels that he holds a more dignified place and the members prefer not to be part of a big machine whose governors they must consult at every twist and turn.

At the same time the fact that in the independent cercles the professor has no governors to check him produces friction between him and members. He is likely to assume that the club exists through and by the glory attaching to his name as a champion of the craft of fence, and prove refractory if the governing committee does not do exactly as he wishes. The members, finding that they cannot convince him—some of the masters are very ill-educated men, with all the obstinacy of the peasant class—and disliking to make a direct breach with a master whom they have learned to like, gradually cease to frequent the salle and accept overtures from their friends to enter another where the master meets their views. In this way Paris is full of fencing clubs weak in membership, kept from actual extinction by the efforts of some teacher who has lacked the tact to accommodate himself to the situation or the good sense to perceive that it was time for him to send in his resignation.

The question of strength as a fencer is very difficult to decide in such a school as that of Joinville-le-Pont, where one may see house after house full of young soldiers fencing with each other for dear life. They are watched by M. Calmels, the professor-in-chief, and by his fellow teachers, MM. Sauze, Rochat and Lemoine. Among amateurs in a place like Paris it is still harder to fix grades of proficiency. Until recently M. Alfonso di Aldama, a Cuban by birth, was generally acknowledged the most perfect in the union of grace and effectiveness. But unfortunately M. Aldama has been in bad health and has practically renounced fencing in public. Among military men M. Fery d’Esclands is cited as a fencer of the first order, but he, too, has practically retired. MM. Vavasseur and Chevillard are admired for the correctness of their pose and delicate work. The Comte de l’ Angle Beaumanoir ranks with Comte de Lindemann for the ” difficulty ” of his method—that is to say, the ability he has to worry his opponent by unexpected positions and vigorous play. Mr. Lewis Halsey Sandford of the club in the Faubourg St. Germain, formerly of New York, is one of the rising amateurs. A fencer who is often seen in public con-tests is M. Alfred Robert, while M. Eugene Caye, a young man still in his teens, is likely to be heard of a few years hence as one of the strongest and most correct amateurs in Paris.

This list is naturally only a mention of a few names, taken partly from club talk, partly from seeing the men fence, partly from fencing with them. But of necessity many who deserve mention are omitted from so short and sketchy an account as can be given here. A very interesting character is that of old M. Popeins Mauffrais, a gentleman born in the French West Indies who goes about with an old maître d’armes and fences daily, not only with his maître but with any stranger who may visit the salle where he is. M. Mauffrais is the privileged of all the floors. All faces smile when his name is mentioned; all heads bow when he begins to chant the heroic lay of his prowess. One year he challenged England to fence with him; another time he sent a formal cartel of defiance couched in the most elegant phrases to all the professors of arms in Belgium. M. Mauffrais is very old but astonishingly vigorous, and is an example of the man who has escaped the wretchedness attending extreme old age by devoting himself to an exercise suited to the feeble as well as the strong. His portrait by Felix Regamey is reproduced, showing him over-whelmed by the attentions of his admirers, who love to test his capacity for applause.

The interchange of ideas in the arts and sciences between nations has gone on since the flood; mankind may be said to advance through the peaceful or hostile shock of ideas; but never before have the sports and games of one nation been taken up by another as quickly and apparently as permanently as we find it the case during the last quarter century with respect to the United States. The games and sports interchanged between our country and France may or may not be destined to endure and become part of the customs of the two nations; but the movement is worth notice.

Although fencing is most practised in North America at New York, its prospects are good elsewhere. At San Francisco, Boston and Philadelphia there are specialists who instruct in the sword; at Chicago, Toronto, Baltimore, Annapolis, West Point and Washington teachers can be had. In many cities the athletic clubs which are being formed place fencing at the head of the sports they propose to cultivate, although for the time being they have no one who is capable to instruct. The fact is interesting as a sign of the estimate very generally placed in America on fencing as an exercise and a game fitted for men, women and children, for private exercise and public exhibitions.