Duelling in Paris [1887]

Child, Theodore. Duelling in Paris. Harper’s Magazine, Vol. 74. Harper & Brothers Publishing. New York, 1887.

Images signed “H. Dupray” likely Henri-Louis Dupray, b. 1841-1909.

Please refer to our Copyright and Usage guidelines.

DUELLING IN PARIS.

BY THEODORE CHILD.

“Honor pricks me on. Yea, but how if honor prick me off when I come on? how then? Can honor set a leg? No. Or an arm? No. Or take away the grief of a wound? No. Honor hath no skill in surgery then? No. What is honor? A word. What is that word? Air….Who hath it? He that died o’ Wednesday. Doth he feel it? No. Doth he hear it? No….Honor is a mere scutcheon, and so ends my catechism.” Falstaff, in Henry IV.

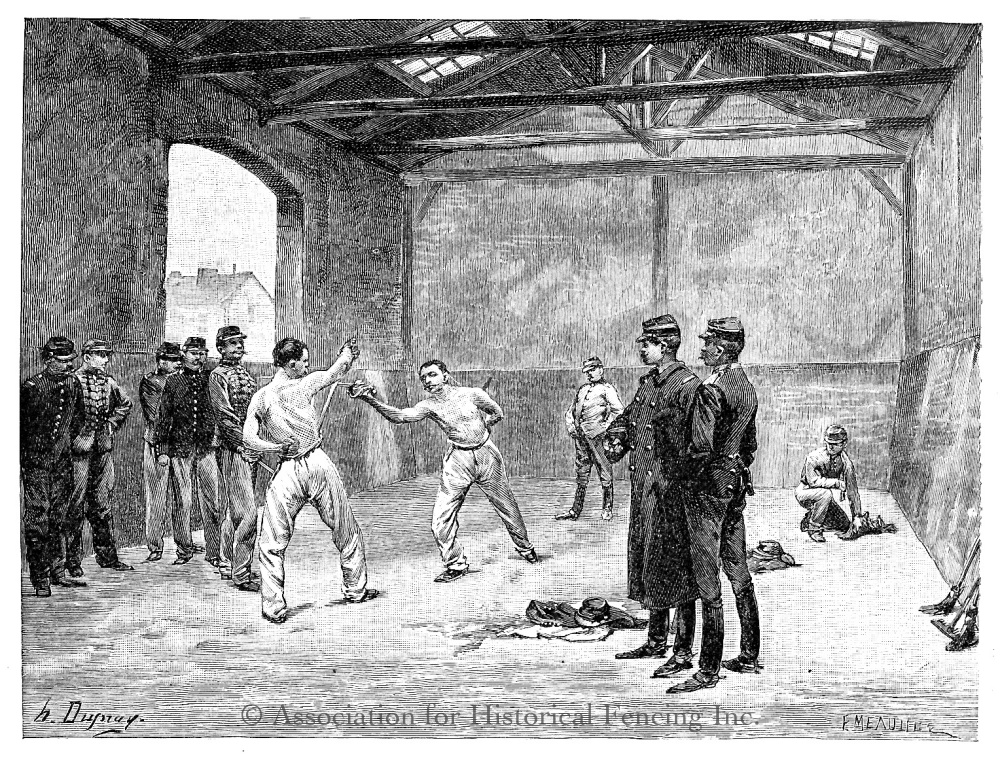

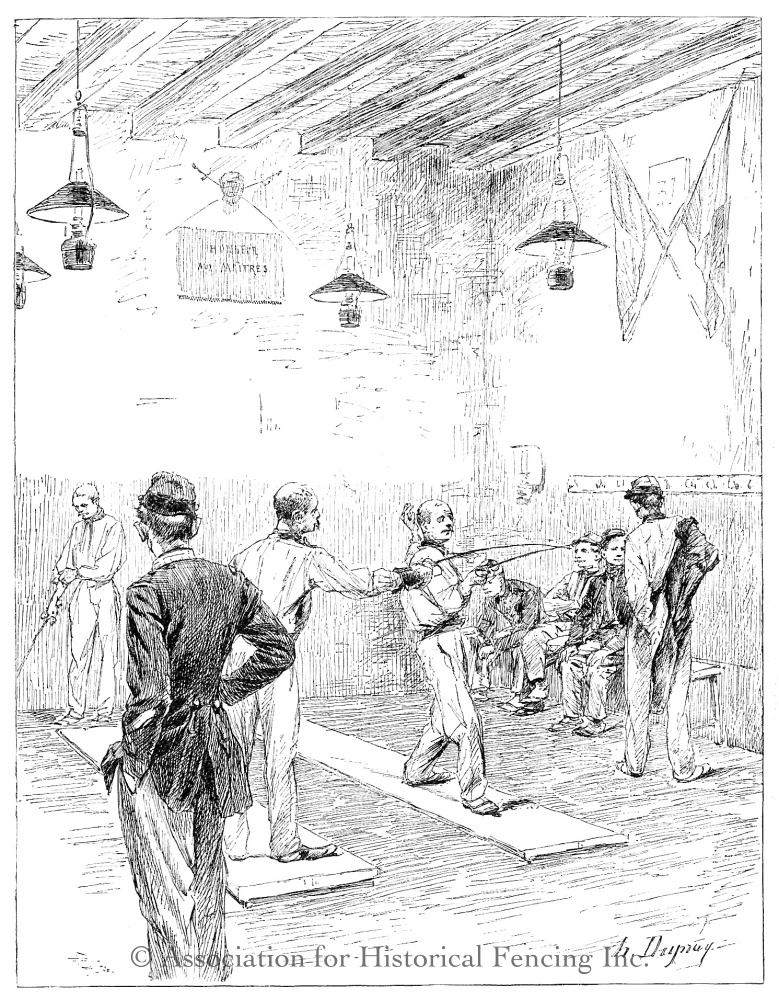

It is not to the credit of the French press, but it is a striking sign of the times, that while you seek in vain in the Parisian newspapers for three lines of honest criticism on a new book, you will find columns of letter-press devoted to the daily chronicle of the race-courses and the salles d’armes. There are assaults at arms, public and private, all over the town ; in the modern Parisian mansion a salle d’armes is considered almost as indispensable as a bathroom ; even at the Élysée Palace there is a salle d’armes, and twice or three times a week the erudite reporters find it their duty to record the thrusts, extensions, parades, counter-parades, feints, disengagements, and ripostes du tac-au-tac, which have been made under the benevolent and paternal eye of the President of the French republic. Never has the rapier been held in higher honor in France than at the present day ; never has the art of fencing been taught with more science, and learnt with greater avidity ; and perhaps never since the times of Richelieu and the Fronde has duelling been more common in France than it is at the present day. Doubtless the light shafts of satire have an easy butt in many a Parisian duel. But when we come to think that, in spite of the successive and severe edicts of Henry IV., Cardinal Richelieu, and Louis XIV., in spite of the elo-quent condemnation of Rousseau and Voltaire, in spite of the prohibition of law and of religion, duelling has remained, since the sixteenth century, not only tolerated but often approved of by public opinion, we may find it interesting to examine the matter seriously to seek the explanation of this curious survival of the practices of chivalry in this prosaic nineteenth century, and to define precisely the role which duelling plays in modern French society.

Old Montaigne says in his Essais, “Put three Frenchmen together in the deserts of Libya, and before a month has passed they will be tearing each other’s eyes out.” One of the chapters of Vital d’Audiguier’s Vrai et ancien Usage des Duels (Paris, 1617) is headed “Pourquoi les souls Français se battent en duel.” In fact, France always has been the great country for duels, and although the French are not the only people who fight duels, they are certainly far more ready to draw their swords than the Italians, the Austrians, the Germans, or the Russians, who are likewise under the tyranny of the institution of duelling. As Buckle has pointed out, duelling is a special development of chivalry, and chivalry is one of the most striking phases of the protective spirit which was predominant in France – up to the time of the Revolution. The French, too, have always been proverbial for their keen sense of honor, their susceptibility, and their pugnacity. In seeking the explanation of the survival of duelling these points must not be forgotten.

To treat of duelling historically would require volumes; the bibliography of the subject, including the art of fencing, comprises some two hundred and fifty volumes, nearly all in French, from the Trattato di Scientia d’arme, published in 1553, and immediately translated into French, down to the various treatises which have appeared in Paris within the past twelve months. Our purpose in this article will be rather to consider only the modern French duel. The reader who wishes to trace the origin of duels from the feudal institution of the judicial duel, or trial by arms, and to read the opinion of the thinkers and jurisconsults of the past, will find all the information he needs in the usual dictionaries and encyclopedias.

The duels of the sixteenth century, of the mignons of Henry III., of the Fronde, and of the eighteenth century will be found recorded with much wealth of detail-in the memoirs of Brantôme, Audiguier, Pierre de l’Estoile, Tallemant des Réaux, Bussy Rabutin, and the innumerable writers of memoirs who succeeded them. In the following pages we shall deal only with nineteenth-century duelling, examining the practice from the theoretical, the social, and the practical points of view, and supporting as far as possible our statements by native and contemporary testimony.

The main-spring and basis of duelling is the “point of honor,” the conception of which varies, not only with circumstances, but with the times. Compare, for instance, Brantôme’s recommendations with the modern code of duelling as laid down by Châteauvillard or by Du Verger de Saint-Thomas. Brantôme says in a curious passage: “The combatants ought to be carefully searched and examined in order to find out whether they have any drugs, enchantments, or spells on their person. Relics of Nôtre Dame de Lorette and other holy things may be worn.” 1

1 In his duel with M. Paul de Cassagnac, who bad challenged him on account of an article which he had written insulting the memory of Queen Marie Antoinette, M. Rochefort owed his life to the interposition of a medal which a female friend had attached to his waistband without his knowledge. The duel was fought with pistols, and M. De Cassagnac said to one of his seconds, “You will see I will lodge my bullet in his waist ; his coat floating in the wind gives me a mark.” M. De Cassagnac aimed as he said ; Rochefort fell, struck at the point indicated. The doctor rushed up, thinking him dead, and drew out from behind the waistband the medal of the Virgin. The ball had gone through the medal, but the resistance had caused it to deviate and merely graze the loins instead of transpiercing the body. M. Rochefort had escaped miraculously. In the Univers of the next day, Louis Veuillot, alluding to a sonnet to the Virgin with which M. Rochefort had won the prize at some jeux floraux, or poetical tournament, in his younger days, wrote these lines : “The Virgin owed you that, Monsieur Rochefort ; but take care in future, for you are now quits.”

Nowadays there is no end to the talk about the loyalty and courtesy of the combat. “There must be no talk of courtesy,” says Brantôme ; “he who enters the lists ought to be determined to conquer or to die, and above all not to surrender ; for the victor disposes of the vanquished as he pleases : for example, he may drag him round the lists, hang him, burn him, hold him prisoner, or dispose of him as a slave.” Horrible barbarity! Rules of a savage epoch, the moderns will say. What will people two centuries hence say of the modern ‘code of honor?

What is the modern French code of honor? What is the point of honor? In practice we find that Frenchmen fight on account of a contradiction, a giving of the lie, a word, a look even, as well as for graver reasons. A duel has come to be the almost obligatory termination of literary and political polemics, and, to tell the truth, honor and the point of honor have had little or nothing to do with many a rencounter of recent years. There has been an abuse of duelling; the practice has been distorted from its primitive and solemn significance ; it has become a fashion, almost a sport, a means for tarnished or tarnishing reputations to get whitewashed, and above all a manoeuvre for obtaining notoriety, especially amongst journalists and politicians.

Indeed, duels between journalists and politicians are so entirely special in their nature and meaning that we may as well speak of them separately. First of all, let us thoroughly comprehend that the traditional point of honor of ancient or modern chivalry has little or nothing to no with them : they are simply the result of professional necessities or prejudices, and in nine cases out of ten the adversaries fight for the gallery—pour la galerie—and for the sake of public opinion. The journalists and politicians are in a measure the gladiators of Paris, and if they do not prove themselves good gladiators, they are liable to be hissed, howled at, harried, and worried until life becomes unendurable. In the career of a French politician or journalist a duel is obligatory. Even Gambetta had to fight. The reader may remember the duel with pistols which took place at Plessis-Piquet, on the plain of Châtillon, in November, 1878, between Gambetta and the Bonapartist minister M. De Fourtou. The adversaries exchanged pistol shots without effect, and an American humorist wrote a comic account of the lethal meeting for the amusement of his countrymen. However, in spite of Mr. Mark Twain’s droll satire, this duel was perfectly serious. The testimony of M. Clemenceau and M. Allain-Targé, who were the seconds of Gambetta, of M. Robert Mitchell and M. Bin de Bourdon, who were the seconds of M. De Fourtou, and the testimony of M. Ranc, of Dr. Lannelongue, and of all the friends of Gambetta, is sufficient to establish that fact.

The cause of the duel was an exclamation of Gambetta during the sitting of the Chamber of Deputies on November 18, 1878—”It is a lie !” (“C’est un mensonge, M. le Ministre!”) These words were addressed to M. De Fourtou, who was making a speech to the Chamber. To say that this exclamation was premeditated would perhaps be going too far; it would be truer to say that Gambetta seized the opportunity of uttering it with joy; he was only waiting for an occasion to pick a quarrel. For some time past the violence of the Bonapartists had been increasing ; their insults in the press had been growing more and more virulent ; and during one of his speeches Gambetta had been interrupted by M. Paul de Cassagnac nearly a hundred times. It was in order to put a stop to this abuse and interruption that Gambetta determined to fight a duel with a prominent member of the Bonapartist party. It was necessary to secure his political position, as Gambetta himself said, when his friends reproached him with thus risking his life. And in point of fact the duel had the desired effect; it gained the respect of the Bonapartists.

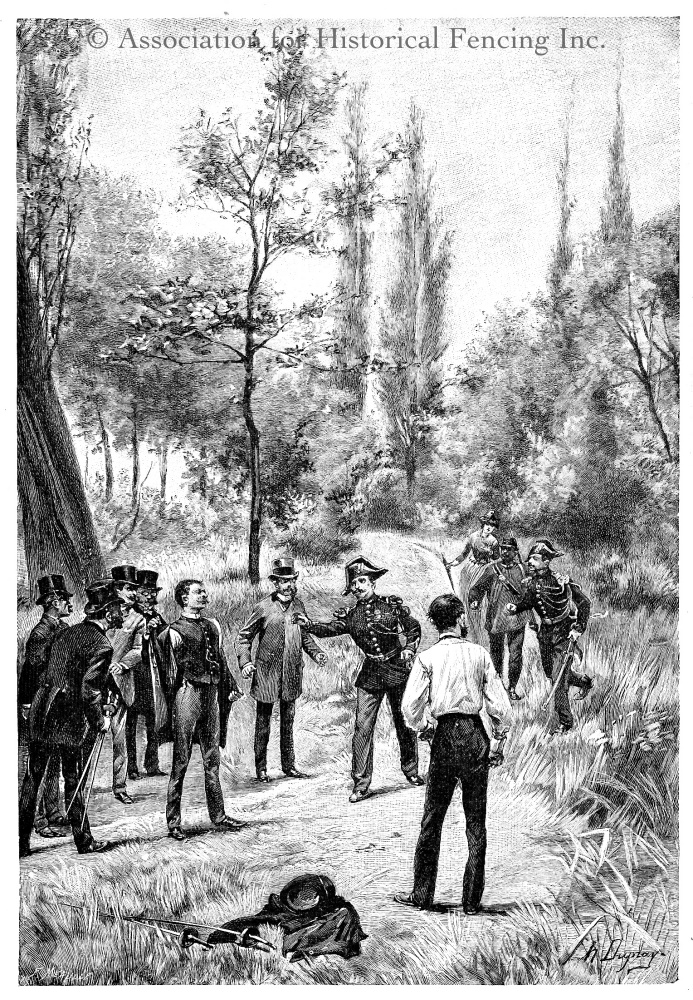

Thanks to the courtesy of M. Clemenceau, I am able to give for the first time the true and faithful history of this duel. After having given the lie to M. De Fourtou, Gambetta left the sitting, and went to look for M. Clemenceau in the lobbies of the Chamber. Gambetta asked M. Clemenceau to act as his second, but the latter refused, not caring to accept the responsibility of such an affair, for, naturally, had anything serious happened to Gambetta, the seconds would have had to bear the brunt of public blame. However, Grambetta insisted. “If you refuse,” he said to M. Clemenceau, “I shall not be able to find a single man to serve as my second. Thiers fought a duel. I must fight too.” Finally M. Clemenceau accepted, and it was he who arranged the whole affair, charged the pistols, and gave the word of command—”Feu! un, deux, trois!” The adversaries were placed at a distance of thirty paces in an open space on the plain of Châtillon, where there was neither tree nor house nor any object in sight of importance enough to guide the aim ; the silhouettes of the combatants stood out against a perfectly clear sky, for the report that the duel was fought in a fog is untrue; the pistols were charged with the regular quantity of powder and with regular bullets by M. Clemenceau himself. M. Clemenceau chose pistols as the arms of his principal, for the simple reason that he did not consider Gambetta to have sufficient agility to fight with swords. As for distance, M. Clemenceau had at first proposed thirty-five paces, but the seconds of M. De Fourtou suggested thirty. Gambetta himself would have fought at five or ten paces, had his seconds ordered him to do so ; but there was an excellent reason for separating the adversaries by as great a distance as possible, namely, the fact that Gambetta was a very large man and M. De Fourtou a slender man. Now supposing the adversaries fired at a distance of five paces, the slender man would have a larger target than the large man ; at ten paces the slender man’s advantage would be lessened, and so on ; the greater the distance between the combatants, the more equal their chances became, as far as concerned the target to be aimed at. Now it being one of the chief duties of the seconds to equalize the chances of the combattants, and to compensate for each one’s advantage or disadvantage, M. Clemenceau was right in demanding thirty-five paces and accepting thirty. It has, I know, been objected that the pistols ordinarily used in duelling would not carry thirty paces. In reply to this objection I may cite a duel fought in 1878 between M. De la Rochette, a Conservative Deputy, and M. Laisant, a Deputy of the Left. The arms were pistols ; the distance thirty-five paces. M. De la Rochette was struck in the thigh by a ball which had force enough to transpierce him, and he died shortly afterward of his wounds. M. Laisant was struck in the region of the heart, and his life was only saved by the floating of his overcoat in the wind, which deadened the impetus of the bullet. As M. Clernenceau, who has fought his share of duels, and acted as second in more than twenty affairs of honor, told me, when you see the muzzle of a loaded pistol pointed at you, even at a distance of thirty-five paces, it seems unpleasantly near.

Throughout this duel Gambetta acted with perfect coolness. On the eve of the engagement M. Clemenceau gave him some hints as to the correct manner of using his arm and aiming. The next morning, when he went to carry him to the rendezvous, he found Gambetta sitting at his window and calmly shooting with a revolver at the sparrows in his garden. While they were riding out to Plessis-Piquet, Gambetta wished to smoke, but M. Clemenceau prevented him, saying that the tobacco would make his hand unsteady. Gambetta’s first words, when the duel was over, were, “Ah! now light up a cigar.”

In duels of this kind the questions of honor and of persons fall entirely into the background. I will cite as an instance the duel with swords fought near Paris on October 10, 1884, between M. Henri Rochefort and Commander Fournier, the author of a treaty between France and Tonquin, which was hotly discussed by the French press. Rochefort wrote a smart and ironical article on the commander in his newspaper L’intransigeant. The commander demanded explanations ; M. Rochefort refused ; a duel was arranged, and both combatants were slightly wounded. Thereupon Commander Fournier and M. Rochefort shook hands, and the latter said to his adversary: “It was neither the man nor the naval officer that I attacked in your person, but simply the functionary of M. Ferry.” This method of combating a ministry whose opinions one does not share is certainly curious; but it is nevertheless a fact that nowadays both in French politics and in French journalism lethal weapons have to be recognized as the auxiliaries of the tribune and the pen.

On this point I will cite an interesting letter which I have had the honor of receiving from M. Henri Rochefort, containing in brief his opinion on duelling.

“Paris, October 1, 1884.

“Monsieur et cher confrère :

“Duelling, the absurdity of which is evident, is a product of Catholicism. The believers of former times imagined naively that the victor was in the right, and that the vanquished was in the wrong, because both had undergone the judgment of God.

“The atheists of the present day cannot consider the duel as anything but the demonstration of their bravery or of their sincerity. When a man fights, he as good as says that he is ready to risk his life to support his opinions. But it is nevertheless true that in most cases a hostile meeting is simply a repetition of M. De Bismarck’s maxim, ‘La force prime le droit,’ inasmuch as it is the best swordsman or the best shot who gets the upper hand.

“However, this kind of exercise has now entered so profoundly into our habits that, in order to put an end to it, there would be needed nothing less than a new Richelieu to have the two adversaries decapitated.

“Receive, etc.

HENRI ROCHEFORT.”

As for the vast majority of duels between journalists in Paris, they are confessedly absurd. Two writers carry on a controversy in their respective journals for a few days; then suddenly one ceases to discuss the other’s assertions, and calls him a “blackguard,” or a “coward,” or an “impudent scoundrel.” A duel ensues; more ink than blood is spilt, and honor is declared satisfied. Whose honor? What satisfaction? Such duels tend to bring the press into discredit, and these journalists, while they amuse the public, win neither its respect nor its sympathy. Still, the insult having been inflicted, public and professional opinion exacts the spilling of blood, or at any rate the simulacrum of that phenomenon. The absurdity, however, of the majority of these professional duels, as they may be called, is so obvious that many eminent journalists propose, in the interest of their profession, the formation of a sort of tribunal of honor composed of brave and loyal men of all parties. Every quarrel would be submitted to this tribunal, which would determine whether a duel was necessary or not, after examining carefully, not only the causes and the forms of the quarrel, but the situations and conditions of the combatants. Soult, when insulted once in the tribune, replied that since he had become a Marshal of France he only fought with cannons. The proposed tribunal would not allow a whole life of honor and labor to be risked for the satisfaction of the brutal and insolent caprice of some beginner anxious to attract attention to his début; and although without legal value, the authorization of this tribunal would have great weight before justice in case of a disaster, and in the eyes of public opinion it would certainly be peremptory. However, although this project has frequently been discussed of late in the French press, it is not Iikely that it will be realized immediately. In France public opinion moves slowly, and the duel ad ostentationem unfortunately serves the purpose of the intriguers and adventurers who form a considerable element in the curious masquerade of Parisian life.

In the duels between French gentlemen there is always a question of the point of honor, whether of the real point of honor or of a false point of honor. According to the duelling code now accepted as laid down in the Nouveau Code du Duel of the Comte du Verger de Saint-Thomas, “all acts, words, writings, drawings, gestures, blows, which wound the self-love, delicacy, or honor of a third party constitute an offence,” and authorize a demand of reparation by arms. Naturally the gravity of offences of each kind is difficult to determine ; the offence is just precisely as grave as one feels it to be, and a man feels an offence in a thousand different manners. That depends upon his temperament, his education, and the rank of society to which lie belongs. In France, for instance, although every man is a soldier, and although in the army duelling is obligatory, the peasants settle their quarrels with nature’s weapons rather than with the sword, while the vast majority of the men of the middle classes would never think of exchanging pistol shots with the first man who happened to eye them in an offensive manner. On the other hand, let us take a famous duel fought in 1873, of which the following is the history. One night the Baron Georges de Heeckeren was sitting in the stalls of the Variétés theatre, when a celebrated demi-mondaine, Caroline L— , with whom the baron was on cool terms—after having been on the warmest—entered one of the boxes on the arm of a Russian gentleman, accompanied by his friend the Prince Dolgorouki. The demi-mondaine, as she took her seat, recognized her ex-lover, and said, “Ah! there is Heeckeren.” Prince Dolgorouki, who only knew the young gentleman by reputation, levelled his opera-glass and leaned over the edge of the box to look at him. Heeckeren, thinking that the company in the box were quizzing him, left his seat and went and knocked at the door of the box. Prince Dolgorouki opened the door, and excused himself for having yielded to a simple impulse of curiosity ; but the irritable baron would listen to no excuses, and slapped the prince on the cheek. A duel was arranged, with the following peculiarly severe conditions : “The combatants shall be placed at twenty paces ; at the word of command each may advance five paces and fire as he pleases; an unlimited number of balls shall be exchanged, and the combat shall not cease until a serious wound shall have rendered its continuation impossible ; the wounded combatants may fire in the position in which they may find themselves when they have fallen; they may also drag themselves up to the limit of the five paces above mentioned, but without the help of their seconds.” Curiously enough, these conditions, imposed by the Prince Dolgorouki, were the same in which the Baron de Heeckeren’s father had fought with the Russian poet Pouchkine in 1837. The duel took place in the Duchy of Luxembourg ; each combatant at once advanced five paces, and at a distance of ten paces both fired, and Prince Dolgorouki fell, his right shoulder shattered. The Baron de Heeckeren went up to his wounded adversary and said to him, “Prince, I am more sorry for my stupidity of the other day than for my address to-day : pardon me for both : you would have received my apology long ago if I had been able to present it.”

This duel was absurd, but no more absurd than most of the duels between Parisian gentlemen who may be classed under the category of viveurs, or “men about town,” as they are called in England. The young bloods of Paris are always ready to draw their swords for a look or a word, or for the approbation of a worthless mistress. The combat in such cases is seldom as serious as the one just mentioned, but the ground is nearly always as frivolous. The only excuse for duels of this kind and a poor enough excuse too—is that it is the fashion to fight. An affair of honor gives a young man a certain notoriety ; the boulevard journals publish an official report of the duel, signed by the seconds; the adversaries are heroes of a certain category for a few days, and their generally harmless escapade excites a degree of curiosity and sympathy amongst the members of the fair sex.

In practice the institution of duelling is undoubtedly greatly abused in France ; nevertheless there are often serious duels, and the theory of duelling is seriously accepted, false as it is. It is a custom which has entered so deeply into French manners that it is not easy to foresee even its obsolescence. In a well-known Parisian newspaper, L’Evénement, there appeared recently the following appreciation of duelling “In France everybody fights, or is liable to fight, and no one thinks of contesting the legitimacy of duelling. Reparation by arms renders more service to social order than a police magistrate and a tribunal of justice. On leaving the courthouse the offender and the offended still retain the feelings of hatred which brought them there. The poisoned words of the lawyers have merely added to the anger of the parties, and resentment thus left smouldering in families may bring about tall kinds of complications and criminal acts. In a meeting on the terrain the case is different. Whatever the result of the combat, whether the ball be lost in the branch of a tree or fixed in a shoulder, whether the sword penetrate the breast or be stopped by a rib, there is an end of the matter. The offence is washed out, and there is no judgment, no decision, so good as the procès-verbal in which the seconds declare honor to be satisfied. The duel is a convention which not only has force of law, but which is even superior to the law, inasmuch as the judge can only give satisfaction to one of the parties, whereas the seconds send away both parties acquitted, and without the possibility of there being any ulterior reproach.”

This is a fair statement of the views of France of the nineteenth century on the subject—views which have been expressed not only in the press, but in legislative assemblies. In the time of Napoleon I. a bill for the suppression of duelling was presented in the Conseil d’Etat, and rejected after discussion, one of the reasons for not taking any legislative action in the matter being the following : “There is a multitude of offences which legal justice does not punish, and amongst these offences there are some so indefinable, or concerned with matters so delicate, that the injured party would blush to bring them out into broad daylight in order to demand public justice. In these circumstances it is impossible for a man to right himself otherwise than by a duel.”

Guizot declared, in the tribune of the French Parliament, “French society must give up the idea of preventing a duel which has a just ground.” Berryer, Brillat-Savarin, Jules Janin, Walsh, Lemontey, Chatelain, Armand Carrol, have defended duelling as an institution which three centuries of legislation and philosophy have been powerless to dethrone. It is a prejudice, a relic of barbarism, or whatever you may please to call it. That they will admit, while at the same time arguing to show that it is necessary for the existence of societies. Jules Janie says, “I would not consent to live twenty-four hours in society, such as it is at present established and governed, if duel-ling did not exist.” There is hardly a name illustrious in the political, literary, and social annals of France during the nineteenth century which is not the name of a duelist. Even the magistrates themselves fight duels. In fact, throughout the century duelling has continued in France as a social scourge, varying in intensity according to the greater or less intensity of the passions of the moment. Now, as in the times of Louis XIV., justice is powerless to suppress the practice, and legislators seem to have abandoned the attempt to do so, or even to regulate duelling.

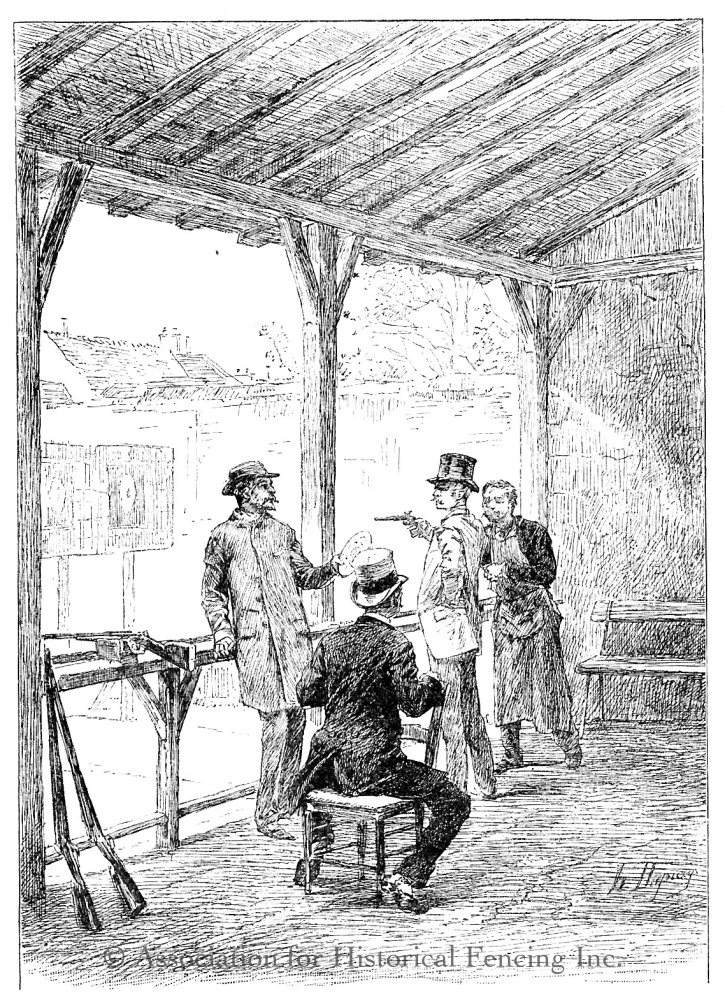

The French duel is a single combat between two or several persons, who fight voluntarily, for some private interest, in accordance with a previous agreement, and in consequence of a challenge in the form of a cartel, the motive of which is some offence. The offence having been given and taken up, the principals choose their seconds, who arrange the whole affair, discuss the interests of their clients, establish the conditions of the duel in all its details. The rights, duties, conduct, of principals and seconds are stated with great minuteness in the Comte de Château-villard’s Essai sur le Duel, and with still greater minuteness in the recent work of the Comte du Verger de Saint-Thomas already cited. It would be outside our purpose to enter more deeply upon the subject of these technicalities, which occupy in the last-mentioned volume some three hundred pages. It will suffice to say that the usual arms are the rapier, the sabre—used almost exclusively in the army—and the pistol ; that before the meeting the conditions of the encounter are minutely detailed in a procès-verbal signed by the seconds ; and that upon the encounter another procès-verbal is drawn up recording the result, and signed by the seconds and by the doctors. Nowadays duelling has become so thoroughly tolerated that the adversaries rarely take the trouble to go to the frontier to fight. They meet in the environs of Paris in a wood or a country lane; several duels have been fought behind the tribunes of the race-courses of Longchamps and Auteuil, and in the presence of numerous witnesses. The police or the gendarmes have a right to interfere and prevent the fight, but in reality these functionaries are rarely at hand at the critical moment. The adversaries, too, may be prosecuted, but except in cases of fatal results justice generally ignores the incident of a hostile encounter, in spite of the publicity given to it by the newspapers.

Considering the frequency of duels in France, one cannot help being a little astonished at the small number of fatal issues. MM. Rochefort, De Cassagnac, Aurélien Scholl, and many other well-known Parisians have to their credit each fourteen or fifteen duels at least, and not one of them is at all maimed by his wounds. There are three reasons why the modern duel is seldom fatal. In the first place, the point of honor demands only a spot of blood, except in altogether extreme cases; the ordinary duel is au premier sang, ”at first blood,” and the duel à mort, the mortal combat, is a rare exception. In the second place, the art of fencing; as now taught is an art of defence rather than of attack, and a good fencer fighting against another good fencer in a conventional duel will simply vie with his adversary in the skill and address he will show in giving a pin scratch with a broadsword. Thirdly, it is the duty of the seconds to see that every combat takes place correctly and according to the rules, and the second to whom is allotted the delicate task of umpire, or juge de camp, has the right to stop illicit or even too dangerous strokes. Generally speaking, the duel with swords in modern times is a mitigated and gentlemanly combat. As we have already seen, it is looked upon as a necessary evil, and it is considered the duty of all concerned in a duel to do all in their power to diminish the fatal results by equalizing the chances of each adversary as far as possible. Now in this equalization of chances the umpire, or juge de camp, plays a very important role. The moment the two combatants are face to face and sword in hand, the duties of the juge de camp begin ; it is he who directs the fight, watches the strokes, suspends an engagement, orders rests, calls time, etc.

We may say, with all respect for the Frenchman’s delicate sense of honor, that in most French duels the adversaries are not in terrible earnest, and do not desire to kill each other outright. For this reason the favorite arm is the rapier, and not the pistol. The duel with swords has been refined to such a point that it may be re-arded as a sort of gentlemanly act of defence. The ordinary French conventional duel bears the same relation to a serious mortal combat as a court sword does to an army sword ; it is almost an affair of etiquette, an exercise which has been rendered comparatively free from danger by the art of fencing, just as the art of dancing and deportment has enabled the courtier to walk without tripping up with his velvet scabbard between his legs. Naturally the maîtres d’armes have a profound contempt for pistols, and all who take a humanitarian view of duelling dwell upon the fact that with the pistol there is no alternative between atrocity and ridicule. The sword is satisfied with a few drops of blood, but it must have those few drops. The pistol sheds floods of blood or nothing at all. Grisier in his treatise on duelling adds to the above arguments the significant remark that all doctors are agreed that it is easier to save the life of a man who has been wounded by a sword than of one who has been wounded by a pistol ball, and “in spite of the horror of the phrase ‘at first blood,’ it must nevertheless be admitted that there is humanity in this convention.” In France the pistol is generally regarded as the arm of the insulted party who does not know how to handle a sword, or who is inferior in a too marked degree to his adversary.

On the other hand, many sensible Frenchmen who are conscious of the absurdity of the duel pour rire, of the frivolity of the majority of conventional duels, and of the truth of M. Rochefort’s opinion that in an engagement the chances are never equal, and it is invariably the better swordsman who conquers, take a more favorable view of the pistol.

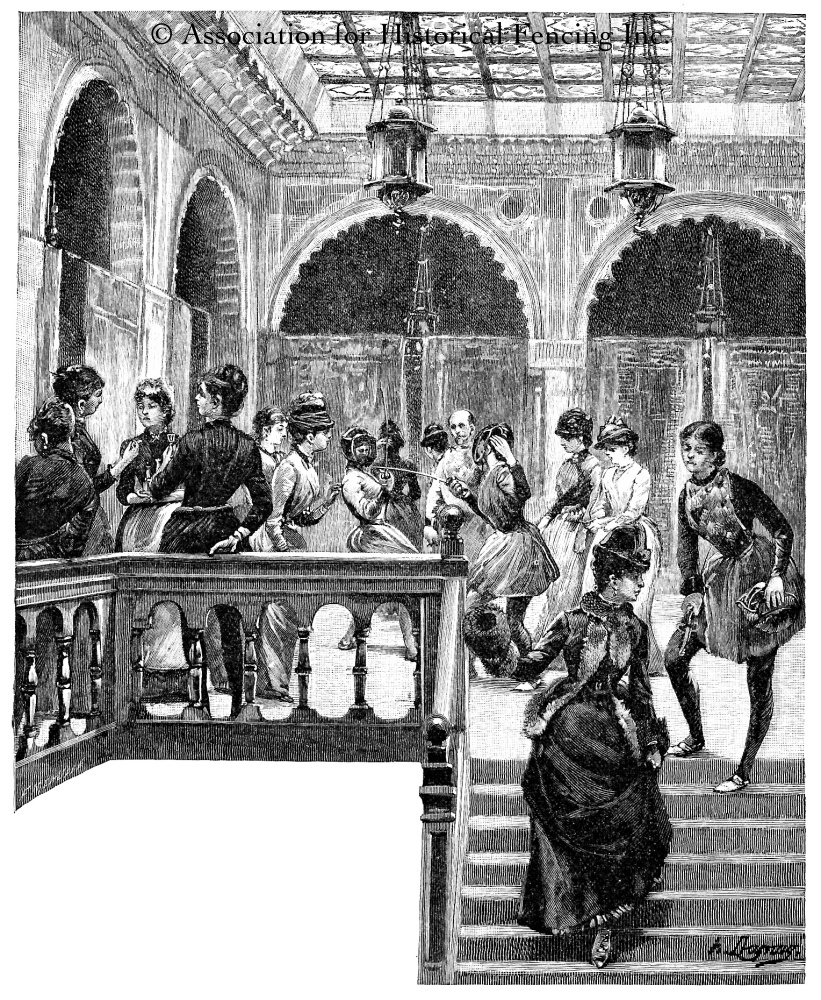

The limits of this article will not allow me to study the Parisian maîtres d’armes and the physiognomy of the fencing schools and their habitués, the celebrities of l’escrime française, amongst whom are men like M. Legouvé, of the French Academy, M. Carolus Duran, the painter who has succeeded General Ney (Duc d’Elchingen) as president of the École d’Escrime Française, the Prince de Broglie, the eminent lawyer M. Fery d’Eselands, the painter Alfred Stevens, M. Banc, the éminence grise and secret dictator of the Republican party, the Comte Potocki, M. De Aldama, the poet and dramatist M. Jean Richepin, M. Delpit, the novelist, and many other Parisian notabilities of art, letters, science, and elegance. The comic types, too, would have demanded a few lines : the young men who come to the fencing school because it is fashionable, but who never touch a sword; the tireur pour cause de ventre, who toils and sweats by order of his doctor, and combats with lethal weapons his own obesity. I should have wished also to have referred to some of the serio-comic duels, such as that fought by the famous critic Sainte-Beuve against M. Dubois, of the Globe newspaper. When the adversaries arrived on the ground it was raining heavily. Sainte-Beuve had brought an umbrella and some sixteenth-century flint-lock pistols. When the signal to fire was about to be given, Sainte-Beuve still kept his umbrella open. The seconds protested, but Sainte-Beuve resisted, saying, “I am quite ready to be killed, but I do not wish to catch a cold.” Sainte-Beuve was finally allowed to fire from under his umbrella, and four balls were exchanged without result. Then, again, I would have introduced the reader some morning about seven o’clock into a little private salle d’armes in the Avenue de l’Observatoire, where the novelist Alphonse Daudet zealously and regularly fences with his eldest son or with a prévôt d’armes before sitting down to his desk. We might also have taken a peep into the salle d’armes of the Conservatoire de Musique et de Déclamation, where we should have seen Jacob giving lessons in fencing to young actresses, future rivals of Dejazet, who was a favorite pupil of Grisier, and in the past of Ninon de l’Enclos, who was a correct swordswoman, and of the famous dancer La Maupin, who killed five or six gentlemen in sword duels in the reign of Louis XV. We might have followed other maître d’armes in their morning calls, and found them teaching society ladies how to bind the blade, and parry, and make counter-disengagements ; and at the head of our list of lady fencers we should have placed Mlle. Fritz, Mlle. Basset, daughter of a Parisian maître d’armes, and Mlle. Jean-Louis, daughter of the famous professor of Montpellier, of whom the latter two married aristocratic pupils, and have become respectively Comtesse de— and Madame De Lezardière.

Fencing is a thoroughly French accomplishment, and at the present time, as I have already intimated, it is the most elegant and fashionable of sports in France, and considered absolutely indispensable to a gentleman’s education. From the social point of view, both fencing and duelling, within certain limits, are held to be perfectly correct, and in the upper ranks of society the man who fights for his honor, or even for a hot word, does not bring himself into the slightest discredit ; on the contrary, he simply shows that he knows how to conduct himself according to the prejudices and usages of his caste—in short, as a gentleman, en galant homine. The eminent Academician M. Ernest Legouvé says that fencing is as much a French art as conversation. “What is fencing?” he asks. “It is conversing; for what is conversing? Is it not attacking parrying, replying, touching above all, if you can? The Germans have their sabres, the Spaniards their knives, the English their pistols, the Americans their revolvers, but the sword is the French arm. Porter l’épée, tirer l’épée, are phrases which you will find, with all their somewhat swaggering signification, in our language alone. Of these two phrases one expresses a gentleman’s right, the other a gentlemanly movement ; both have in them something elegant, chivalrous, and vainglorious which depicts a trait of our character, and is intimately bound up with our social traditions.” M. Legouvé’s desire is to have the French democracy remain aristocratic in manners, and nothing, he thinks, could be of more avail in the realization of this wish than the handling of the sword. “Has not the sword the finest of all privileges?” exclaims the worthy Academician. “It is the only arm which can avenge you without bloodshed.” Instead of killing the man who has insulted you, you simply punish him by disarming him, says M. Legouvé.

So long as intelligent and influential Frenchmen continue to conform their conduct to the deep-rooted prejudices concerning duelling, and so long as they continue by their acts and writings to defend the existence of this convention, which the most superficial examination shows to be based upon a whole series of mistaken notions of right and justice, so long, too, as duelling is obligatory in the army, it is not likely that either legislation or public opinion will succeed in bringing the practice into discredit. It must be remembered, however, that in modern France duelling is only practised by a very small part of the population. Indeed, ever since it was introduced by the Franks duelling has existed as an institution only amongst a small portion of humanity, and in this small portion it has always been the appanage of a pretentious minority. As for the French duel of the present day, generally based upon trifling and often silly grounds of offence, it is, as the journalist Aurelien Scholl says, “a mania of the epoch which has hitherto not brought about great disasters.”