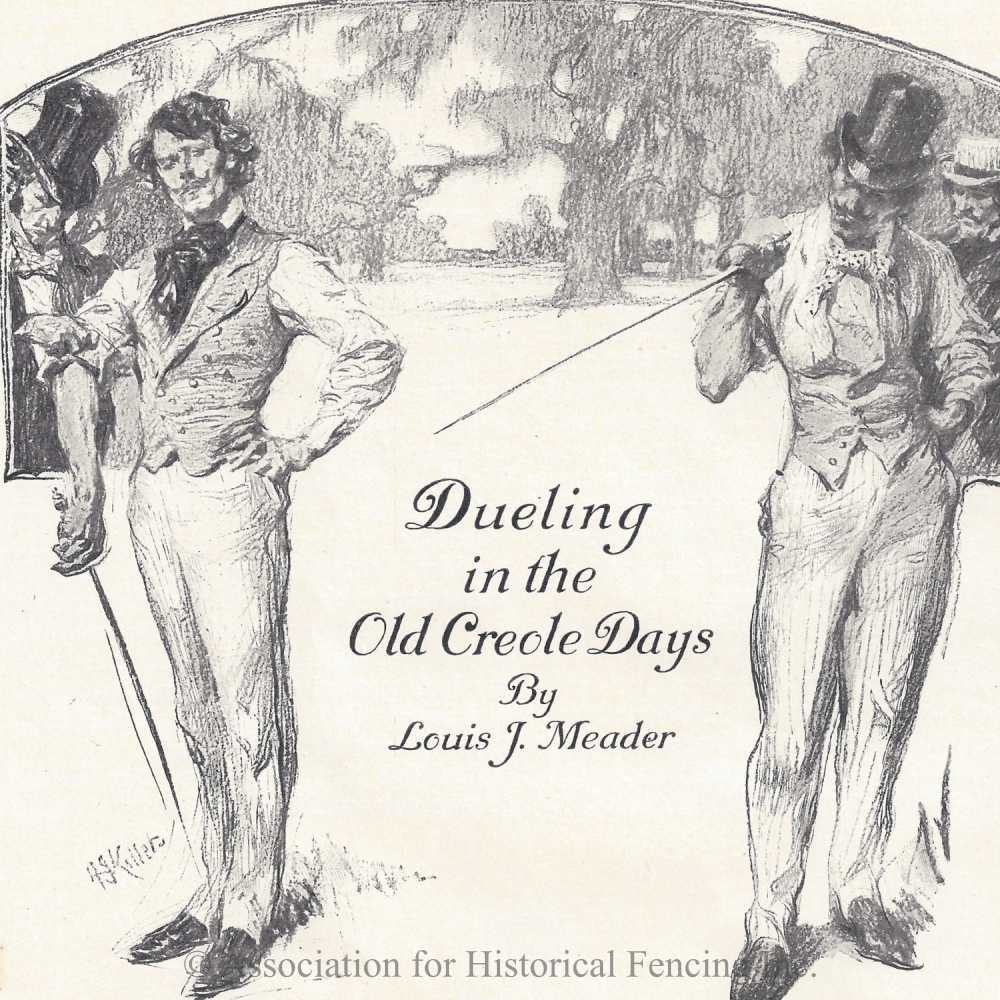

Dueling in Old Creole Days

Dueling in Old Creole Days. Meader, Louis. Century Magazine. Volume 74, Number 2. June, 1907.

Images drawn by Arthur I. Keller and Henry Fenn.

Please refer to our Copyright and Usage guidelines.

Just where and when the first affaire d’honneur took place is not known, and obviously cannot ever be known. Homer makes frequent reference to single combat, and the story of David and Goliath is only added biblical testimony that duels were known to the early Hebrews and other ancient Asiatics, as they were known to the Arabs at the time of Mohammed. It remained, however, for the barbarians who overran the Roman Empire to apply the first touch of poetry to what had previously been mere brutal conflicts, for they conceived the idea that a wager of battle was an appeal to the decision of the gods and that success was a proof of right.

In this unique theory undoubtedly existed the germ from which subsequently sprang the “code duello,” and certain it is that the even more ancient Idea of blood atonement also played a part in the establishment of a system that served to throw a magnetic glamour about the heroes of the Middle Ages and to link itself inseparably with the romance of those chivalrous times. The day of dueling, however, has long passed; the gallant knight, riding afar, full armored and alone, in quest of blood to spill for the redressing of wrong, has retired behind the shadowy veil of history, and his shirt-sleeved counterpart of a later period has likewise disappeared beyond the horizon of the past.

Absurd buffoonery has supplanted the real combat, the significant à la mort has vanished from the modern cartel, and but for an occasional, if not isolated, exception, the affaires of our generation savor much of the comic opera and seem to suggest clogs rather than buskins.

When dueling was an actual factor in the social order of this country it had many worthy and notable exponents, including no less distinguished personages than Henry Clay, Andrew Jackson, Alexander Hamilton, DeWitt Clinton, Stephen Decatur, and others of the same type; but nowhere on this continent was it so much an established institution as in that peculiarly romantic old city of New Orleans. It was woven into the very fabric of the life of the community, and many a crumbling tombstone in the antiquated Creole cemeteries bears grim and silent witness to the fact, though to understand the situation more clearly one should breathe, so to speak, the atmosphere of the period.

New Orleans, while somewhat cosmopolitan even at that time, was essentially a Creole city and under the full influence of traditions that governed that high-strung and chivalrous people. The descendants of the early possessors of the soil—many of whom were of noble birth—gradually metamorphosed into a characteristic race, a distinctive type, constituting a condition unparalleled in the history of this country. What with education in common, intermarriage, the habit of command acquired from the ownership of slaves, and the refining tendency of well-employed leisure, a form of aristocracy was established. To this Louisiana owes much of its romance and many of its most brilliant intellects.

Partly by birth, but largely by manners, breeding, education, and tradition, it was a kind of nobility, and life in the “Crescent City” was a poem of luxury and ease.

New Orleans was not only a great seaport, but, owing to its river facilities, not then antagonized by the railroads, controlled the entire trade of the Southwest with virtually no competition. Money was obtained without the demoralizing effect of continuous labor; time was left to employee as well as to employer for mental and ethical culture; and imagination was not by the very nature of things excluded from the active world.

The women, reared at home under the jealous guardianship of a mother, and educated for the most part in convents, and invariably treated with the most deferential gallantry by the men, had naturally acquired manners and tastes of great refinement. Society was of courtly brilliancy, merchants and professional men were incidentally poets and wits, and many were accomplished musicians.

Over all this there reigned an almost feudal dignity and a supreme sense of honor, maintained by a strict and unflinching public opinion. The etiquette of the day demanded that bankrupts commit suicide and that fallen women disappear forever; society then permitted no compromise with honor.

Under such conditions, the punctilio among men was carried almost to the point of exaggeration, and the least breach of politeness or the slightest insinuation of unfair dealing, even a bit of awkwardness, was deemed sufficient cause for a challenge. The acceptance, however, did not necessarily mean that a duel would inevitably result; the seconds, two selected by each principal, met and discussed the case dispassionately, sometimes the assistance of a common friend was obtained, and not infrequently an honorable and amicable adjustment was effected.

A blow in retaliation for an insult was not only strictly forbidden, but sufficed to debar the striker from the privilege of a duel. A gentleman who could so far forget himself as to strike another in resentment was ignominiously denied a meeting, and some whose self-possession deserted them at the critical moment have been known to submit to great humiliations in order to obtain from their adversaries a cross of swords or an exchange of shots.

Even an insult was not permitted to go beyond a certain decorum of form, and experienced friends, well versed in the code and its precedents, settled beforehand every point of nicety, so that when gentlemen met on the field, they did so in full equality.

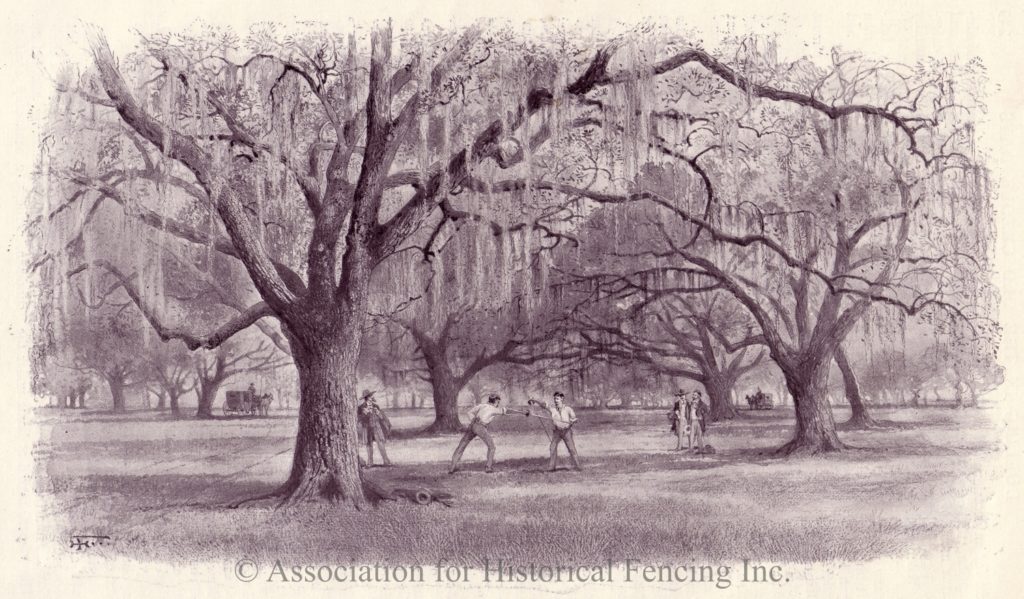

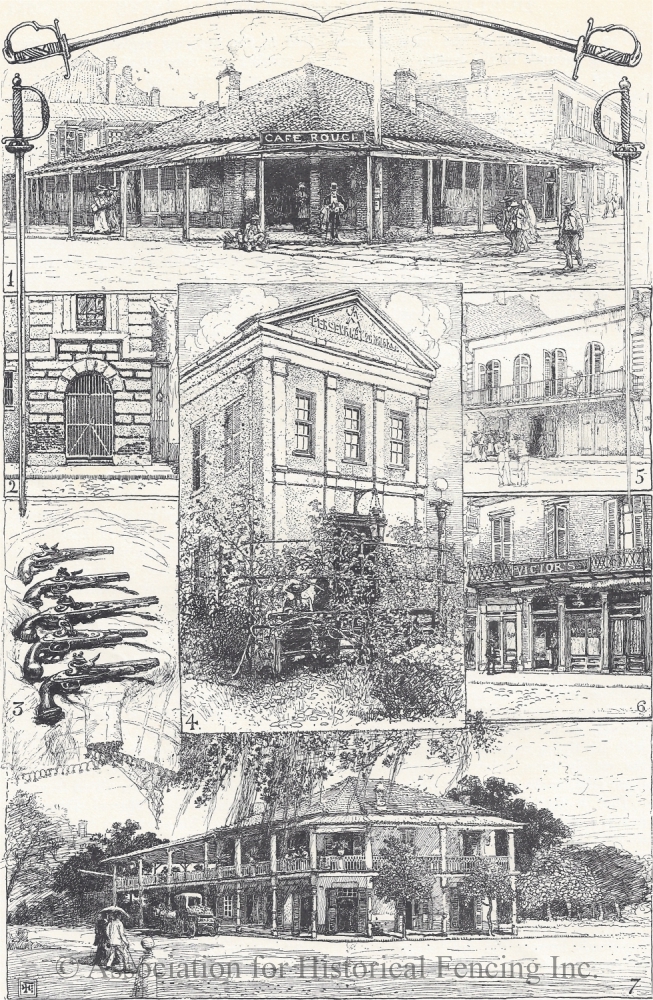

Many a bloody combat had its provocation at ball or opera, where the cause of the difficulty passed unobserved; but the offender was certain to receive a challenge the following morning, and before sundown, perhaps, a neat coup droit at “The Oaks,” one of the most famous dueling-grounds in the world.

This picturesque though melancholy spot now forms one of the show-places of the Creole city, and they must be more than callous who are not susceptible to the poetic influence of that magnificent grove of forest giants, preserved to this day in all its primeval grandeur—Nature’s monument to a dead and well-nigh forgotten past.

What is now Lower City Park was formerly a portion of a wooded plantation belonging to Louis Allard, a scholarly gentleman and a poet. The original tract was extensive, but the portion that now constitutes the park proper, and which includes The Oaks, passed out of his hands through foreclosure sale, and was purchased by John McDonogh, the eccentric millionaire miser and philanthropist who endowed almost the entire public school system of New Orleans.

At McDonogh’s death the land was left jointly to the cities of Baltimore (his birthplace) and New Orleans, the latter acquiring full possession at the partition sale.

During the latter portion of his life, Allard, whose inclinations were more literary than commercial, grew wholly indifferent to business, and, becoming crippled in health and fortune, was permitted by special agreement to continue his occupation of the place after the sale. There, under his beloved oaks and among his favorite authors, he spent his declining years, although he did not long survive the sale of his estate, and, in accordance with his dying request, was buried under the stately trees, where a weather-worn tomb still marks his resting-place.

Just a stone’s throw from Allard’s grave, rearing their patriarchal heads in solemn grandeur, stands the particular grove of trees known the world over as The Oaks, and under the protecting boughs of which ebbed the crimson life-tide of many a brave and noble fellow.

The “Chênes d’Allard,” as they were familiarly known, did not become a rendezvous for duelists until the year 1834; prior to this the favorite field was on the old Fortin property (now the Fair Grounds), where the regular winter race-meet takes place. As a matter of fact, New Orleans being then but thinly settled in the outlying regions, there were a number of convenient places where duels were regularly fought without interference. Indeed, there existed a law against the practice, but so strongly was it entrenched in the customs of the people that the statute served only to add a mysterious glamour to the other fascinations of the deadly game, and, so far as effectiveness went, might as well never have been enacted.

Under such conditions it is not surprising that New Orleans became a Mecca for maîtres d’armes, most of whom had no personal standing beyond their skill with weapons, and hence lived in a sort of whirl of wine, blood, and profligacy, dividing their time between fencing-rooms and their favorite cafés. The names of many of these swaggering fellows are now forgotten; but there were some of them who regarded their calling as an honored profession, and by their skill in arms, manly characters, and lovable traits, won for themselves not only the respect of the community, but a certain amount of social recognition. Prominent among this class was E. Baudoin, a Parisian, who in his day was exceedingly popular. Emile Cazère also had an aristocratic clientèle; and Gilbert Rosière was probably the favorite of all the fencing masters who ever appeared, in New Orleans. There was also a mulatto, Basile Croquère, who was so excellent a swordsman that, notwithstanding the indelible color line, many of the most conservative Creole gentlemen did not hesitate to attend his salle d’armes or even to cross swords with him in private.

Others whose fame rested chiefly upon their having killed or been killed in some celebrated duel were Marcel Dauphin, who disposed of his adversary in a combat with shotguns; Bonneval, who was killed by Reynard, also a professional swordsman; L’Alouette, who killed the fencing-master Shubra; and Thimécourt, who, in a broadsword encounter, cut his opponent, Poulaga, to pieces.

The maître who left the best, and certainly the most vivid, record, however, was Rosière, and many of the old inhabitants of the Crescent City still mention with feeling the name of that gay, whole-souled, though irascible fencing-master who answered Beauregard’s call and followed the Orleans Guards to Shiloh.

A native of Bordeaux, he went to New Orleans when young, with the avowed intention of winning fame and fortune at the bar; but being of reckless disposition, he fell in with the devil-may-care set and, deserting the Code Napoléon for the code d’honneur, became a fencing-master, and incidentally the leader in all the escapades and adventures of the “golden youths” of that time. During the Mexican war, he made a fortune teaching officers the art of fencing, although he squandered it as lightly as it was made. He was brave and generous to a fault, and, paradoxical though it may seem, this hero of seven duels in one week was every one’s friend, and, in many respects, was as kind and gentle as a woman. He loved battle and would fight men to the death, but would never harm a defenseless thing, and was particularly fond of little children and dumb pets. A passionate lover of good music and delicately sensitive to its melting impressions, his massive shoulders and superb head could be seen almost nightly at the opera, towering conspicuously above the others about him.

Once when deeply touched by the pathos of a well-sung cantilena, he was moved to tears, which brought a laugh from an unfeeling coxcomb in the opposite chair. Instantly Rosière’s tenderness turned to anger. “I may weep,” said he, “but I also fight.” The next day the impudent fellow was taught by sad experience that one does not always grow fat by laughing.

Never a day passed without one or more encounters at The Oaks or other dueling-grounds about the city, and the spirit of the age is expressively summed up in Don César de Bazan’s terse words: “Quand je tiens un bon duel je ne le lâche pas.” (“When I have a chance to fight I do not let it slip.”)

In the spring of 1840 a grand assaut d’armes between professional swordsmen took place at the old Salle St. Philippe, which was crowded to its utmost capacity, though only graduated experts were permitted to take part. On this occasion a diploma was as necessary as in the practice of medicine. Pépé Lulla, a valorous young chap skilled in the use of several weapons and afterward famous for a large number of successful duels, was refused the privilege of a bout because he had no papers to show. Some time after that he challenged a French professor named Bernard, who had insisted upon his producing a diploma, and with a master stroke of broadsword opened the old fencer’s flank in two places. This same assaut d’armes was the cause of Thimécourt, formerly a cavalry captain, and Poulaga, an Italian professor, fighting a memorable duel. The latter, a veritable Hercules in strength and stature, was there holding his own with a broadsword and bidding defiance to all-comers until opposed and defeated by Thimécourt. This was too much for the Italian’s pride, and he remarked with a sneer that his adversary was a fair beginner. “Qu’à cela ne tienne,” (“Never mind”), retorted the soldier; “let us adjourn to the field,” and without further parley they repaired to The Oaks, where the depreciating Italian was hacked to death at his own game—broadswords. Thimécourt became one of the most noted professors of fence of that period, and upon another occasion had some slight difference with a well-known contemporary named Monthiach, who was rather fleshy and one of the best-natured fellows imaginable,but always ready for a duel, especially with a professor.

Wherever there is skill there is jealousy; but the old maîtres d’armes were particularly and aggressively jealous of one another, and as the point at issue in this instance was a “coup,” and they disagreed completely, the “logical” way of coming to an understanding was to fight it out; that is, applying the system of logic that prevailed in such matters in those days. Well, they fought with broadswords, because the disagreement was about that weapon, and the duel was short and decisive. At the first pass Monthiach made a terribly vicious cut at his adversary, evidently intending to decapitate him at one blow, and though the coup was admirably conceived and executed, Thimécourt who had his own idea, did not parry, but dodged. His hat was cut completely in two, Monthiach’s blade just grazing his scalp; at the same time he passed under the other’s sword and reached his chest with a splendid coup de pointe. They had taken no surgeon with them, and the seconds interfered; the gash was a frightful one, and the blood flowed freely from it, yet Monthiach insisted upon proceeding with the fight.

The seconds, however, would not permit it, and, to the horror of the bystanders, the wounded duelist drew from his pocket a wad of tow, which he calmly stuffed into the cut to staunch the blood, and walked home in a frenzy, cursing the seconds who had stopped the fight. He declared that his was a beautiful coup, and that he would certainly have whacked off Thimécourt’s head had he been given a chance to renew it.

Another affaire that is characteristic of the manners and customs of the period was between M. Pedesclaux and M. Augustin, the former a tall, muscular, athletic young fellow, a favorite in society, and quick-tempered and skilled in the use of arms, and the other a rather slender young lawyer, a great student and devoted to his profession, but also fond of the military.

Both were members of a crack artillery company, and Augustin, who had recently been made a lieutenant, was rather proud of his glittering uniform and trailing artillery saber. Parade had just been dismissed when Pedesclaux came up to his friend and, in a spirit of semi-ridicule, gave the swaggering weapon a knock with his foot, at the same time saying: “What could you do with that thing?” Quick as a flash came the reply: “Follow me to The Oaks, and I will show you.” Not another word was said; each selected two friends to act as seconds, and proceeded to the scene of combat.

Augustin was a mere youth, with little experience in such matters, while his antagonist was in the prime of manhood and an accomplished swordsman; but the battle had scarce begun when the latter received a cut on his sword-arm that rendered him helpless, and, as the seconds interfered, the incident closed with a rollicking dinner at Victor’s.

A while after this, Pedesclaux had a serious quarrel with a retired French cavalry officer who also enjoyed a reputation as a duelist; the cartel was passed with due dignity, and the Frenchman, having the choice of weapons, selected broadswords on horseback.

It was a vicious but handsome combat: both were mounted on blooded stallions and stripped bare to the waist, and as they rode up to each other, nerved for the battle, their muscular development and bearing were positively classic. The Frenchman was a little the heavier of the two and gave evidence of remarkable strength and endurance; Pedesclaux, although lighter in weight, was admirably proportioned, and his youthful suppleness seemed more than to counterbalance the other’s brawn.

With a clash of steel that drew sparks from the blades, the two antagonists crossed, and passed each other unhurt. In another moment both horses had been wheeled about by their expert riders, who faced each other again. A terrible head blow from the old cavalryman would have cleft the other to the shoulder-blade if a quick movement had not warded off the death-stroke; then with lightning rapidity, before his adversary could recover his guard, which had been disturbed by the momentum of the blow, the young Creole, by a rapid half-circle, regained his, and with a well-directed lunge drove his blade through the body of the French officer, who reeled in his saddle and fell to the ground, dying shortly after.

Another famous duel on horseback was fought with cavalry sabers by Alexander Cuvillier and Lieutenant Schomberg, U. S. A., on D’Aquin green, a little above what was then the village of Carrollton, but which is now a portion of the city proper. After the second pass, Cuvillier made a vicious cut at his adversary, which, falling short or otherwise being miscalculated, severed the jugular vein of Schomberg’s horse, which died on the spot. This put a stop to the duel, and some time afterward Cuvillier died.’ His brother Adolphe, who had charge of the succession, received a letter from Schomberg recalling the duel and stating that the horse killed in the fight belonged to his colonel, and that he had been required to make indemnity to the extent of five hundred dollars, further hinting that it would be proper for Mr. Cuvillier to pay at least half.

Adolphe replied that as testamentary executor of his brother’s estate he had charge of all his affairs, including this quarrel, and that he would cheerfully send a check for two hundred and fifty dollars, and would even be willing to pay full price for another horse if the lieutenant would agree to renew the fight with him. He never received an answer.

Augustin, to whom previous reference has been made, and who afterward became a district judge and general of the Louisiana Legion, was the victor in several other encounters in which the temper of the period caused him to be engaged. One in particular is noteworthy on account of the part it played in an extraordinary freak of fortune. Alexander Grailhe was the offending party, though the insult (or rather provocation, for gentlemen seldom insulted) would in this day be of scant concern. But some cause of action was present, and each was sure that a deadly meeting would certainly follow. They rode together in a carriage with ladies, who, after the duel, commented on their mutual affability during the entire trip, which only serves to show how delicately adjusted was the code of etiquette—especially in the presence of ladies.

They fought at The Oaks, and as soon as the weapons had been crossed and the impressive “Allez, Messieurs,” pronounced, Grailhe, who was high-strung and hot-blooded—doubly so under the stress of what he regarded as a grievous provocation—lost his temper and furiously charged his antagonist. Augustin, on the contrary, was cool, collected, and agile, parrying each savage thrust, until by a temps d’ arrêt (sudden pause), judiciously interpolated into a vicious lunge of Grailhe’s, he pierced him through the chest. Grailhe, with one of his lungs perforated, remained for a long time hovering between life and death, and when at last he did come out of his room, he was bowed like an octogenarian.

It was now only a question of time for the wounded man, as an internal abscess had formed where it could not be reached, —surgery then was not what it is now,— and the doctors despaired of saving him. Some time after he had been up and about, a quarrel with Col. Mandeville de Marigny resulted in his challenging that distinguished citizen. This duel was also fought at The Oaks, but as Grailhe was too weak to do himself justice with a sword, the weapons chosen were pistols at fifteen paces, each to have two shots, advance five paces, and fire at will. At the first shot, fired simultaneously, the unfortunate man fell forward, pierced by his adversary’s bullet, which had entered the exact place of his former and yet unhealed wound. Marigny, with pistol in hand and as placid as a marble statue, advanced to the utmost limit marked out, when Grailhe, who was suffering greatly, exclaimed: “Fire again; you have another shot.”

With grave dignity Marigny raised his pistol above his head and fired into the air, saying with frigid politeness: “I never strike a fallen foe.”

More dead than alive, the stricken duelist was carried home by his friends and consigned to the care of his physician; but instead of sinking rapidly, as was expected, he really began to mend, and by the following morning was much improved. The ball had penetrated to the abscess which had threatened his life, and made an exit for its poisonous accumulations. Some time afterward he walked out of his room as erect as ever, and soon regained his health and stately bearing.

Another case that illustrates the determination with which a desire for satisfaction was pursued when once the breach was made, is that of Frank Yates and Joe Chandler. This duel took place in 1859 and was arranged for The Oaks; but the police authorities interfered at that point, and the principals and seconds retired to another spot near Bayou St. John. Here again they were confronted by officers of the law, and by this time it was getting late, heavy clouds were gathering overhead, and an occasional falling drop suggested a strong probability of rain.

What with this condition of affairs, the melancholy song of katydids, and the croaking of frogs in a neighboring swamp, the situation was far from pleasant. Matters were urgent, however, so the party betook themselves to their carriages and drove to a place just on the outskirts of the city. Darkness had now settled down, and a fine drizzling rain added to the gloom of the surroundings and the dismal appearance of things generally; but there, under the flickering light of an old-fashioned street lamp, pistols were loaded, handed to the principals, who were placed at short range, and the command was given to fire.

After an ineffectual exchange of shots, Chandler’s seconds made an effort to settle the matter peaceably, but were repulsed by the others, and the affair was allowed to proceed. At the third shot Yates reeled backward and fell, dying a few days later.

New Orleans has always been a music-loving city and is specially fond of the opera, which it maintains through a long season annually. It is part of the Creole nature to be extreme in all things, and their taste in this particular respect amounted almost to a passion. Out of a mere discussion over the relative merits of different singers has grown many a fatal combat, and it would require vastly more space than the narrow limits of this article to chronicle even a small part of the duels that were the product of hostility engendered by the opera. A case or two in point, however, will suffice.

During the season of 1857-58, an exceedingly bitter feeling existed between two stars of the French Opera troupe, IVIlle. Bourgeois, a contralto, and Mme. Colson, a light soprano. The enmity was occasioned by the latter’s having replaced as “chanteuse légère” a young woman of great beauty and excellent voice, who was unpopular with the public, though a very dear friend of the contralto, who resented the substitution.

On the occasion of her benefit night, for which she had selected Massé’s opera of “Galatée,” the title-rôle of which properly belonged to Mme. Colson, Mlle. Bourgeois went outside her company and asked the deposed “chanteuse,” who was still in the city giving music lessons, to sing the part. When this became known, it caused considerable discussion and no little feeling among opera patrons, many of whom felt outraged at what they regarded as an open insult to Mme. Colson, and declared they would not allow Mlle. Bourgeois’s friend to sing. She, on the other hand, had her following, who were equally pronounced in their views, and publicly avowed that all those who hissed would regret it. In those days such a threat was sufficient to produce a legion of hissers.

One evening a short while before the performance in question was to take place, a number of gentlemen were lounging about and practising with foils at one of the salles d’armes ; Gaston de Coppens and Emile Bozonier, two of the most popular young fellows in the city, were with the others, and the conversation naturally drifted to the all-absorbing topic of the day. Some one asked Bozonier if he did not intend lending his lusty voice to the proposed hissing; but the issue was of no particular concern to him, and as he was interested in something else at the time, he answered, in a sort of preoccupied fashion, that he thought any man who went to the theater for the sake of hissing a woman was a blackguard and should have his face slapped.

“Do you know,” retorted De Coppens, his face growing pale with anger, “that I have proclaimed myself one of those who will hiss that woman down?”

“I do not,” replied the other, in the same deliberate tone; ” but I nevertheless mean what I said.”

“Would you slap a man’s face if he hissed on that occasion?”

“If he were close enough to me, I most assuredly would,” answered Bozonier, now becoming aroused and interested.

“Well,” said De Coppens, “you will have your hands full,” and there the matter rested until Mlle. Bourgeois’s benefit night.

The old opera-house was packed to its limit, and to even a casual observer it was evident that a feeling of suppressed excitement pervaded the entire auditorium; every one seemed to realize that beneath the gay and glittering surface there burned a smoldering and dangerous fire.

This state of feverish agitation continued until that part where the curtain covering the statue is drawn aside, and Galatée begins to live and move; then, as though by common accord, there arose such a din as was probably never before heard in such a place and the like of which, let us hope, will never be heard again.

Applause from one faction, hisses and jeers from the other, each trying to drown out the other, combined to create a bedlam that could be heard far into the street. There, amid the growing tumult, calm and unmoved, the one self-possessed creature in that vast throng, stood the innocent cause of it all, undaunted and •without faltering, singing her numbers through to the very end.

Little, indeed, did anybody hear of Massé’s music that evening. Most of the ladies retired after the first clashing outburst, and more than one quarrel begun on that eventful night was concluded next day on the field of honor. That, however, is digressing.

De Coppens had kept his word, and though separated from Bozonier by a dense crowd, their eyes met and a look of defiance passed between them. A few days later they met by chance on the street, and with a sneering smile the former said: “Well, Monsieur, what became of those slaps?”

For a reply he received a stinging smack that sent him spinning, and but for his splendid mastery of himself would have precipitated matters then and there. A challenge followed quickly, and Bozonier, being skilled in the use of neither rapier nor pistol, chose cavalry sabers.

They met at The Oaks, and scant ceremony characterized the opening of the encounter. The first pass showed clearly the fierce fires of animosity that burned within the hearts of both, and the seconds’ instructions that the fight was to last until one or the other should be completely disabled seemed wholly superfluous.

Bozonier made a rush at De Coppens and feinted, then, taking advantage of his adversary’s effort to parry, quickly passed over his sword and made a swinging stroke at him that would certainly have brought a sudden termination to the struggle had not De Coppens, by a rapid movement, warded off in part the effect of the blow. As it was, the point of the saber slashed De Coppens’ cheek and sank deep enough into his chest to fell him to the ground. It was a terrible gash, and for a moment rendered him completely at the mercy of his foe, whose generous nature prevented his following up the advantage.

A momentary pause, and he sprang to his feet like a wounded tiger, reaching Bozonier’s sword-arm with a vicious lunge and rendering him almost helpless. Then the battle went the other way; for, with the muscles above the elbow severed, Bozonier could scarcely grasp his weapon, and before the seconds were able to appreciate the danger of the overwhelming handicap, Bozonier fell, bleeding from half a dozen terrible wounds. Both, however, recovered, owing to their splendid constitutions, and fought with equal valor in the Civil War. De Coppens became colonel of a Louisiana regiment and was killed in the battle of Seven Pines.

A month or two after the duel just referred to, a violent criticism from the pen of Emile Hiriart, a vitriolic writer, appeared in one of the local papers; the same day he received challenges from two gentlemen who had taken exception to his article, and with characteristic spirit he accepted both.

The first was settled without serious results, through action on the part of the seconds, but the other was quite a different affair. This one was with E. Locquet, and the fact that an underlying hatred existed between the two accounted no doubt for the deadly purpose displayed in the choice of weapons—double-barreled shotguns loaded with buckshot, at forty paces. The Creoles were all huntsmen, and in their hands this was indeed a frightful weapon. Seconds rarely permitted its use except in cases of the gravest provocation, as it was no uncommon occurrence for both principals to be killed in such an encounter.

There was necessarily an air of solemnity about the preliminaries of any duel in those days, but on this occasion it was almost funereal as the ground was measured off and the antagonists were placed in their respective positions.

As was customary in such combats, the seconds tossed for the word of command, and Hiriart’s friends won it. As both were excellent shots and men of iron nerve, this was regarded as a considerable advantage. The word was given: “Fire, one, two, three,” and Hiriart fired as soon as the first word left the speaker’s mouth, with Locquet only a fraction of a second behind. Both were struck; the latter, turning completely round and leaping into the air, fell flat upon his face without uttering a sound; his adversary wheeled about, and dropping his gun with the cry, “It is all over,” fell apparently lifeless upon the grass.

Locquet was dead, but the offending critic’s life was saved by his quick shot, which, it appears, did not give the other time, to raise his weapon to the proper level, and, being discharged at an angle, the load merely struck the ground and glanced upward, stunning, but not seriously injuring, Hiriart.

Anything like a complete record of the of duels of that period would be a library in itself, since, for a couple of generations dueling was a daily occurrence in New Orleans, and those who lived in the vicinity of The Oaks declared that for years there was almost a continual procession of pilgrims to that bloody shrine.